Humans put lots of satellites up there — about 1,700 working spacecraft are in orbit around our planet — and not every piece of machinery comes right back when its job is done. Many keep speeding through the sky long after scientists have lost touch, leaving them liable to crash into one another and break into small pieces. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) estimates that there are about 23,000 pieces of space debris larger than 10 centimetres (or about four inches), about 500,000 larger than one centimetre, and about 100,000,000 larger than one millimetre.

A piece of metal smaller than a sesame seed might not sound dangerous, but even these tiny bits can pose a big risk. The International Space Station navigates around the paths of the most dangerous hunks of junk, but tiny flakes of paint have managed to chip the craft’s quadruple-thick windows. That’s because space garbage moves fast.

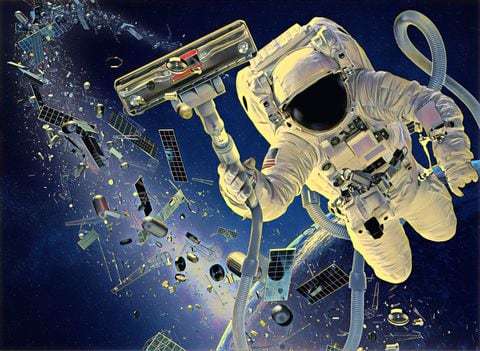

“Because of the super-high impact speed — more than 10 times the speed of a bullet 250 miles up — even a sub-millimetre debris could threaten astronauts when they conduct a spacewalk outside of the International Space Station,” says J.D. Harrington, a NASA public affairs officer.

Small debris can punch a hole in a satellite, while larger debris can crush one entirely — creating even more wreckage.

“The threat from orbital debris is real,” Harrington says. “Because of the ongoing space activities, the orbital debris problem is expected to worsen in the future and will present an even greater danger to future space missions.”

An increase in orbital traffic — it’s becoming easier and cheaper for countries, private companies and research groups to send objects up — means that our corner of space will have increasingly less space.

NASA doesn’t have plans to clean up what’s there, but the agency is working to keep the problem from worsening by ensuring that each new mission includes clear arrangements to dispose of spacecraft that no longer work and any pieces they eject.

And there are potential solutions in the works from others: At the 2017 European Conference on Space Debris, presenters discussed pushing junk off into a higher orbit, capturing it with nets and harpoons or magnets, and other ideas. In May, the International Space Station is expected to deploy a test project called RemoveDEBRIS, which will capture several pieces of pretending garbage before burning itself up in Earth’s atmosphere.

But while we wait for someone to design the ultimate space vacuum, are folks on Earth safe from the danger of falling debris? The short answer is yes. Junk falls down all the time: 200 pieces of debris reentered the atmosphere in 2016 alone. Most of that burns up and breaks down in the process, and the pieces that remain are unlikely to cause harm. Most of the Earth is either covered in the ocean or has plenty of open space, so chances are any hunks of junk will hit spots without humans there to get hurt. There’s only one known case of a human getting hit with a piece of spacecraft — Lottie Williams in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1997 — and she didn’t even get a bruise from the accident. You’re way, way more likely to get struck by lightning.

The Washington Post

More about: space