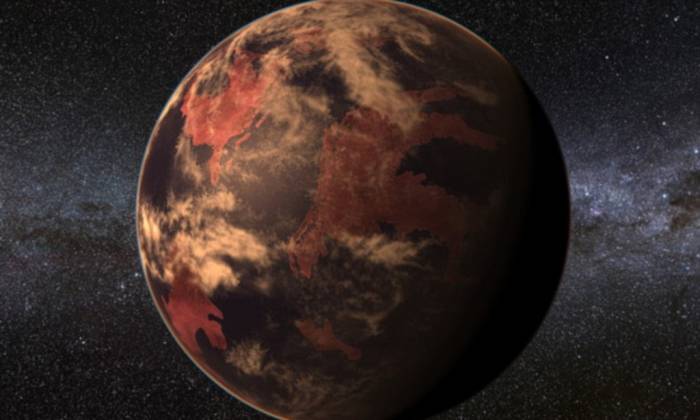

Before this event, the Earth had a soft mantle unable to support large mountain ranges.

But as the mantle cooled, land emerged, and the climate of the planet and it's ability to support complex life was transformed.

Land collisions which rose out of the oceans created the first mountain ranges and plateaus.

Around 2.7 billion years ago, the Earth formed its first super-continent - Kenorland.

Researchers previously thought that the land emerged gradually between 1.1 and 3.5 billion years ago, but this study suggests it was a sudden event.

Temperatures on the surface when the new land emerged from the sea would have likely been hotter than today by several tens of degrees.

At that time, dramatic changes in our climate triggered the creation of complex life Earth, scientists found.

Simple forms of bacteria that only thrived in water were superseded by more complex algae, plants and fungi.

Exposure of the new land to weathering may have set off a sink of greenhouse gases such carbon dioxide.

This disrupted the radiative balance of the Earth which led to a series of glacial episodes between 2.4 billion and 2.2 billion years ago.

A bright surface, provided by emerging land, would reflect sunlight back into space, creating additional torque on radiative-greenhouse balance and a change in climate.

'What we speculate is that once large continents emerged, light would be reflected back into space and initiate runaway glaciation,' Dr Bindeman said.

'Earth would have seen its first snowfall.'

This could also have resulted in the Great Oxygenation Event which ended around 2.1 billion years ago when atmospheric changes brought significant amounts of free oxygen into the air.

Researchers led by led by Ilya Bindeman from the University of Oregon tracked these dramatic changes by looking at chemical changes in shale - the world's most common sedimentary rock.

They took 278 shale samples from outcrops and drill holes from every continent, spanning 3.7 billion years of Earth's history.

In doing so, they established when newly surfaced crust was exposed to weathering by chemical and physical processes.

Daily Mail

More about: science