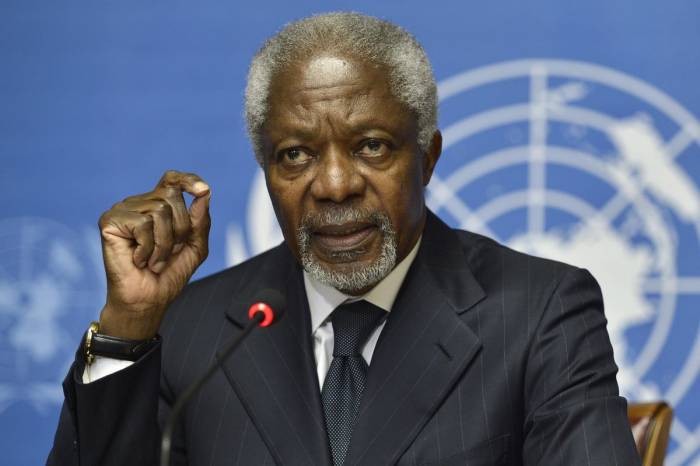

Kofi Annan championed many global causes during his distinguished life and career, but as a native of Ghana, he always felt a special responsibility to Africa. And there, no issue was more important to him than tackling hunger and spurring growth through agriculture.

During his tenure as Secretary-General of the United Nations, Annan, who died last month, often wondered why so much of Africa – with its abundance of fertile land and freshwater – had failed to turn farming into an asset. He even commissioned a study for the UN to analyze why “green revolutions” – agricultural reforms in Asia and Latin America that lifted millions out of poverty and accelerated economic transformations – had bypassed Africa.

That study reached a straightforward conclusion: while Africa’s farmers have the potential to meet the continent’s nutritional needs, they cannot do it alone. The study’s findings led Annan to advocate for a “uniquely African green revolution” to increase farm productivity, and his plea later became the basis for the African Green Revolution Forum. This week, the AGRF – one of the world’s most important platforms for African agriculture – will gather for its annual meeting to discuss ways to help the continent feed itself.

Africa’s agricultural sector has come a long way since 2010, when Annan chaired the first AGRF meeting, in Accra. Today, governments across the continent, including in Rwanda, this year’s host country, have placed agriculture at the center of their socioeconomic policies. This focus is creating jobs and improving food security and nutrition, while innovative partnerships are helping to build more viable, inclusive agribusinesses.

And yet, despite progress, millions of Africans continue to suffer from hunger and extreme poverty. As leaders prepare for another round of AGRF discussions, Annan’s vision of a food-secure and prosperous Africa is more relevant than ever.

Today, five key challenges are impeding Africa’s agricultural progress; each needs urgent attention. First, Africa’s governments must make good on pledges to allocate at least 10% of public spending to agriculture. At the moment, only 13 countries are hitting this mark. Simply put, Africa will continue to fall short of its economic potential if public and private investment in agriculture is not increased.

Second, Africa needs an accountability system to measure policies and progress against key performance indicators. To that end, the African Union should endorse a new African Leaders for Nutrition initiative that is developing scorecards for agriculture and nutrition programs.

Third, regional and international donors must direct more aid to the millions of smallholder farmers who rely on agriculture to make ends meet. Africa’s small farmers can be integrated into agricultural value chains, but not without first increasing farm productivity. To improve yields, smallholder farmers need access to high-quality seeds and fertilizers, innovative financing, and modern technology. Most important, support must be directed to the future of African agriculture – young people and women.

Fourth, the volume of agricultural trade between countries must be increased, which can be accomplished by harmonizing trade regulations, lowering transportation costs, reducing tariffs, and improving warehouse and cold-storage facilities. A more robust intra-African food trade would promote economic growth, attract new investors, create jobs, and help prevent food insecurity.

Finally, everyone involved in strengthening Africa’s agricultural sector – from donors to farmers – must never forget the transformative power of partnerships. Rather than working at odds, Africa’s governments, businesses, financial institutions, NGOs, and farmers’ organizations should pool their resources and expertise whenever possible.

In 2006, when Annan stepped down as UN Secretary-General, he commented that in his next job, people might call him “Farmer Kofi.” Many of his colleagues assumed he was joking; he wasn’t. While his post-UN portfolio ranged from peacebuilding in Syria to political dialogue in Kenya, he never stopped advocating for Africa’s smallholder farmers.

For Annan, the eradication of hunger was not an end but rather a means to creating a more just and peaceful world. As he put it in an interview in 2013, “a hungry man is not a free man,” because he can focus only on his next meal. Now that Annan is gone, it is up to the rest of us to ensure that his vision of freedom for Africa is realized.

Alan Doss is President of the Kofi Annan Foundation and a former under-secretary-general at the United Nations.

Read the original article on project-syndicate.org.

More about: KofiAnnan