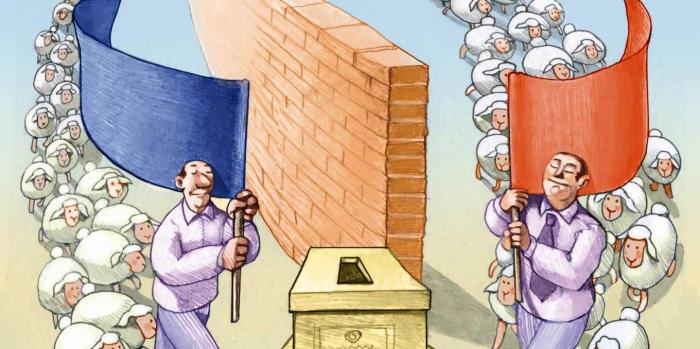

If authoritarian populism is rooted in economics, then the appropriate remedy is a populism of another kind – targeting economic injustice and inclusion, but pluralist in its politics and not necessarily damaging to democracy. If it is rooted in culture and values, however, there are fewer options.

Is it culture or economics? That question frames much of the debate about contemporary populism. Are Donald Trump’s presidency, Brexit, and the rise of right-wing nativist political parties in continental Europe the consequence of a deepening rift in values between social conservatives and social liberals, with the former having thrown their support behind xenophobic, ethno-nationalist, authoritarian politicians? Or do they reflect many voters’ economic anxiety and insecurity, fueled by financial crises, austerity, and globalization?

Much depends on the answer. If authoritarian populism is rooted in economics, then the appropriate remedy is a populism of another kind – targeting economic injustice and inclusion, but pluralist in its politics and not necessarily damaging to democracy. If it is rooted in culture and values, however, there are fewer options. Liberal democracy may be doomed by its own internal dynamics and contradictions.1

Some versions of the cultural argument can be dismissed out of hand. For example, many commentators in the United States have focused on Trump’s appeals to racism. But racism in some form or another has been an enduring feature of US society and cannot tell us, on its own, why Trump’s manipulation of it has proved so popular. A constant cannot explain a change.1

Other accounts are more sophisticated. The most thorough and ambitious version of the cultural backlash argument has been advanced by my Harvard Kennedy School colleague Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart of the University of Michigan. In a recent book, they argue that authoritarian populism is the consequence of a long-term generational shift in values.

As younger generations have become richer, more educated, and more secure, they have adopted “post-materialist” values that emphasize secularism, personal autonomy, and diversity at the expense of religiosity, traditional family structures, and conformity. Older generations have become alienated – effectively becoming “strangers in their own land.” While the traditionalists are now numerically the smaller group, they vote in greater numbers and are more politically active.

Will Wilkinson of the Niskanen Center recently made a similar argument, focusing on the role of urbanization in particular. Wilkinson argues that urbanization is a process of spatial sorting that divides society in terms not only of economic fortunes, but also of cultural values. It creates thriving, multicultural, high-density areas where socially liberal values predominate. And it leaves behind rural areas and smaller urban centers that are increasingly uniform in terms of social conservatism and aversion to diversity.

This process, moreover, is self-reinforcing: economic success in large cities validates urban values, while self-selection in migration out of lagging regions increases polarization further. In Europe and the US alike, homogenous, socially conservative areas constitute the basis of support for nativist populists.

On the other side of the argument, economists have produced a number of studies that link political support for populists to economic shocks. In what is perhaps the most famous among these, David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson, and Kaveh Majlesi – from MIT, the University of Zurich, the University of California at San Diego, and Lund University, respectively – have shown that votes for Trump in the 2016 presidential election across US communities were strongly correlated with the magnitude of adverse China trade shocks. All else being equal, the greater the loss of jobs due to rising imports from China, the higher the support for Trump.

Indeed, according to Autor, Dorn, Hanson, and Majlesi, the China trade shock may have been directly responsible for Trump’s electoral victory in 2016. Their estimates imply that had import penetration been 50% lower than the actual rate over the 2002-14 period, a Democratic presidential candidate would have won the critical states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, making Hillary Clinton the winner of the election.

Other empirical studies have produced similar results for Western Europe. Higher penetration of Chinese imports has been found to be implicated in support for Brexit in Britain and the rise of far-right nationalist parties in continental Europe. Austerity and broader measures of economic insecurityhave been shown to have played a statistically significant role as well. And in Sweden, increased labor-market insecurity has been linked empirically to the rise of the far-right Sweden Democrats.

The cultural and economic arguments may seem to be in tension – if not downright inconsistent – with each other. But, reading between the lines, one can discern a type of convergence. Because the cultural trends – such as post-materialism and urbanization-promoted values – are of a long-term nature, they do not fully account for the timing of the populist backlash. (Norris and Inglehart posit a tipping point where socially conservative groups have become a minority but still have disproportionate political power.) And those who advocate for the primacy of cultural explanations do not in fact dismiss the role of economic shocks. These shocks, they maintain, aggravated and exacerbated cultural divisions, giving authoritarian populists the added push they needed.

Norris and Inglehart, for example, argue that “medium-term economic conditions and growth in social diversity” accelerated the cultural backlash, and show in their empirical work that economic factors did play a role in support for populist parties. Similarly, Wilkinson emphasizes that “racial anxiety” and “economic anxiety” are not alternative hypotheses, because economic shocks have greatly intensified urbanization-led cultural sorting. For their part, economic determinists should recognize that factors like the China trade shock do not occur in a vacuum, but in the context of pre-existing societal divisions along socio-cultural lines.1

Ultimately, the precise parsing of the causes behind the rise of authoritarian populism may be less important than the policy lessons to be drawn from it. There is little debate here. Economic remedies to inequality and insecurity are paramount.

Dani Rodrik, Professor of International Political Economy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, is the author of Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy.

Read the original article on project-syndicate.org.

More about: populism