German principalities intended to establish small colonies in Africa in the 17th and 18th centuries but later they were suppressed by the Netherlands and France. So in 1871 – on the eve of the unification of Germany – the country had no colonies in Africa. Thus, Prussia prioritized the unification of German lands rather than searching for land on the other side of the ocean. As Germany got behind in the world’s colonization, all the territories were divided between Britain, France, the Netherlands and Belgium.

Furthermore, Germany’s financial trouble and the weakness of its navy at that time hindered the country’s imperialist claims. Despite initial hesitations, German businessmen considered the seizure of colonies a promising business. Therefore, the government was supporting such initiatives unless it had no special obligations. Herewith, the Germans turned to lands with a small population and resources that were of no interest to other European countries.

In 1884, the Society for German Colonization, headed by Carl Peters, began to seize East African lands. In 1883, Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz, a merchant from Bremen, acquired about 45,000 kilometres-long area (larger than present-day Switzerland) in present-day Namibia and even received a security guarantee from the German government. After Britain announced its disinterest in Namibia in 1884, Germany declared a protectorate over the latter’s territory. The territory was then named the German South-West Africa and became state property.

After Kaiser Wilhelm II came to power in 1888, Germany’s attitude towards colonies changed. For Germany, the colonization matter became not only a source of raw materials and consumption but a reputation personifying the fact that German was a great power, which, in turn, caused a growing interest in colonies.

Faced with unfavourable weather conditions in Namibia, the Germans began to seize the lands and livestock of the local population, treating them like slaves, insulting and torturing them. The authorities began to ignore the locals’ complaints. In the early 20th century, Germany was considering placing the Herero people in reservations, resettling the newcomers – German colonists – in the territories freed, and bankrupting locals under the guise of credit dependence.

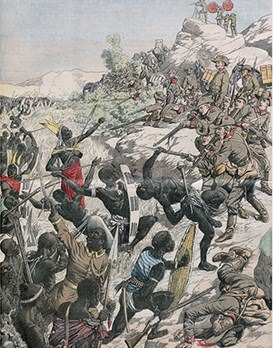

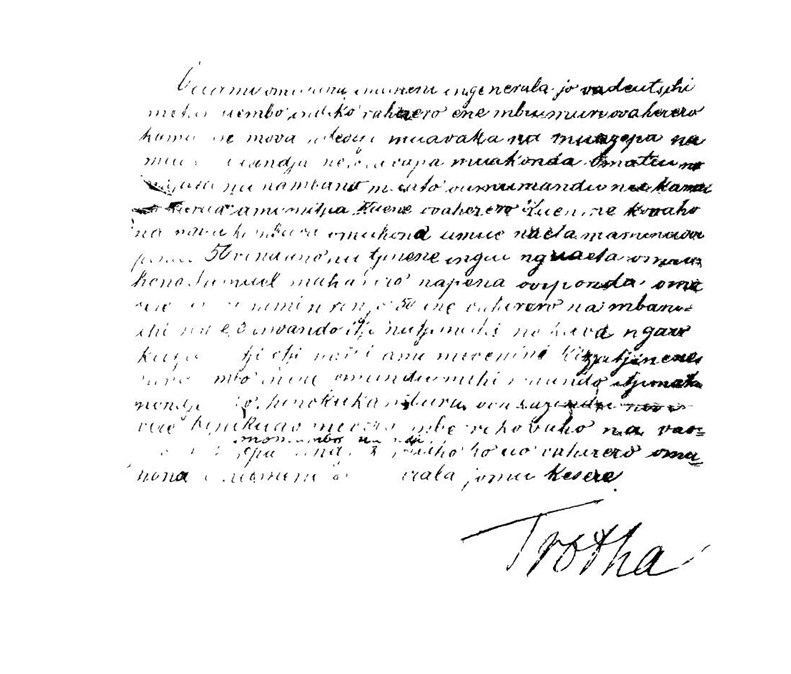

On January 14, 1904, the Herero and Nama people rebelled against the pressure, killing 120 Germans, including women and children. In June, the military command of the German South-West Africa deployed 14,000 troops to quell the uprising. In order for the rioters to be punished, General Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha, who participated in the wars with Austria and France, as well as was directly involved in the suppression of the uprisings in Kenya and China, was appointed military commander of the German army in southwest Africa. Having failed to gain a complete victory in an open battle, the Germans began to pursue the rebel groups in the desert. The Germans forced locals into the desert by surrounding viable land and water sources, which had already led to an act of genocide. Lothar von Trotha completely rejected all talks on capitulation. On October 2, 1904, the military commander issues the Vernichtungsbefehl, or extermination order.

“Any Herero found inside the German frontier, with or without a gun or cattle, will be executed. I shall spare neither women nor children. I shall give the order to drive them away and fire on them. Such are my words to the Herero people,” the general said.

Lothar von Trotha was intending to create a completely “white” territory there.

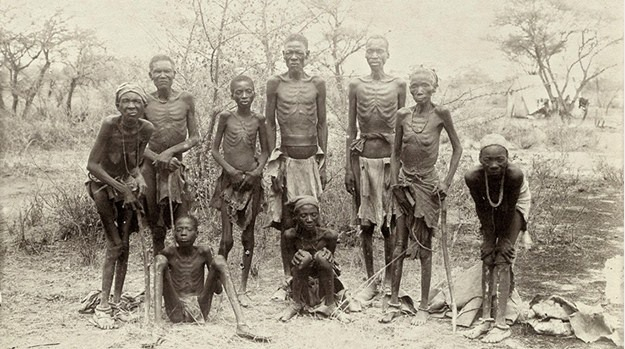

Although the rebels tried to cross the desert to seek shelter in a British colony (the territory of present-day Botswana), they either starved to death or were killed by the Germans. Some rebels lost their lives after drinking water from desert wells poisoned by the Germans. Many Herero people later died of disease, fatigue, and starvation.

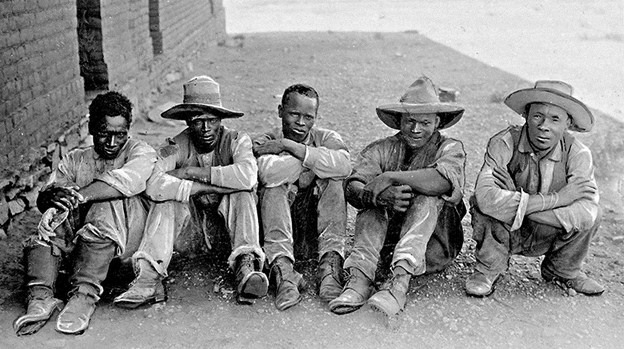

Captive members of the tribe were marked with the letter GH (Gefangener Herero), "captive of Herero." Focusing on the English model in South Africa, the Germans started the implementation of a system called "concentration camps" and established concentration camps. These camps were created in large cities where labour was in demand. Captives were placed in 6 concentration camps. One of the most famous was the camp on Shark Island, close to the harbour town, Luderitz. Only 200 of the 3,500 captives in Shark Island could survive. The death rate in the camp ranged from 45 to 74 per cent.

Also, the food was extremely scarce there. Dead bodies of horses and oxen were given to the captives as food. The disease continued to spread, and they were not provided with any medical care despite being forcibly captived by the Germans under harsh conditions. Slave workers were subjected to shootings, torture, and other cruel treatment. Herero captives, mostly women and children, were rented out to local establishments or forced to work in government infrastructure projects. The captives were exploited as slaves in the extraction of diamonds, copper, in the mining industry and the construction of railways.

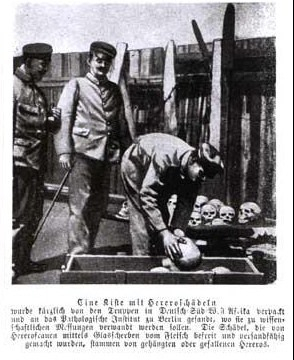

The German scientist Eugen Fischer, Dr Bofinger conducted various experiments on captive in the concentration camps showing the superiority of the white race. The members of the tribe suffering from the bone disease were injected with various substances, including opium and others and then German scientists studied the effects of these substances. Besides, women were used to be raped and killed, and the rest of the tribe were sterilized.

The experiments on corpses were also widespread. Bone and skin samples were sent to German laboratories and museums as exhibits, medical and racist experiments. In October 2011, after three years of negotiations, the first 20 of the 300 skulls kept in the Charite Museum were returned to Namibia for burial. In 2014, an additional 14 skulls were sent to Namibia by the University of Freiburg.

Adolf Hitler became particularly interested in Eugen Fischer's experiments. The Germans used the Concentration Camp method for the very first time in Namibia. Those who experimented with captives later taught Eugenics at German universities. They used this experience gained in Namibia in World War II.

A census carried out in 1905 disclosed that there were 25,000 Herero captives in Germany's South West Africa.

Although the war officially ended on March 31, 1907, the destruction of African societies continued. Some "local decrees" were adopted in 1907, severely restricting the freedom of movement of Africans and forcing them to carry an iron ID card around their necks following the deprivation of the rights of the local population and the seizure of their lands. The Germans were scared of possible African unrest and considered large-scale deportations of African colonial officials in Windhoek and Berlin to German territory in Cameroon and even Papua New Guinea to prevent this threat despite the overthrow of Herero and Nama. However, World War I prevented the implementation of all the plans.

The British government issued a statement on the German genocide against the Nama and Herero tribes after gaining control over the territories in 1918.

There is no exact information about the number population in colonies. Some sources show that the population changes between 70,000 and 100,000.

According to the report by the United Nations, German troops killed 75 % of Herero people, which resulted in a decrease of the population - 15 thousand. During the genocide between 1904 and 1908, more than 80% of the Herero population and 50% of the Nama population of Namibia was wiped out by German soldiers.

Müxtəlif mənbələrdə müxtəlif sayda şəxsin qətlə yetirildiyi yazılsa da, qəzetlər Almaniyanın 2004 -cü ildə soyqırımı tanıdığını elan edərkən 65 min qurban olduğunu qeyd etdi.

Although the number of victims of the massacre is written differently in various sources, newspapers write about the recognition of the genocide by Armenia with 65,000 victims.

According to the report by United Nations in 1985, the Herero and Nama genocide was the first genocide of the 20th century. In the UN report, this massacre was assessed as an act of genocide similar to the massacre of Jewish people by the Nazis.

In 1998, German President Roman Herzog visited Namibia and met Herero leaders. Chief Munjuku Nguvauva demanded a public apology and compensation. Herzog expressed regret but stopped short of an apology. He pointed out that international law requiring reparation did not exist in 1907.

In 2001, members of the Herero tribe in Namibia sued Deutsche Bank, Woermann Line and the German Government in US court seeking reparations for genocide. It was the first time that an ethnic group had demanded compensation for its colonial policy in accordance with the legal definition of genocide. In order to overcome legal and political obstacles, claimers wanted sympathy from the people by drawing attention to the parallel between the genocide committed against their ancestors and the genocide committed by the Nazis against the Jews. However, on March 7, 2019, a New York federal court has dismissed a lawsuit by the Herero and Nama tribes seeking compensation from Germany for the genocide of their ancestors.

In 2004, on the 100th anniversary of the genocide Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul, who was Federal Minister for Economic Cooperation and Development of Germany at the time, apologised and expressed sorrow over a colonial-era genocide. “We Germans recognize our historical, political, moral and ethical responsibility and guilt," the development minister said.

She ruled out paying special compensation but promised continued economic aid for Namibia in the amount of 14 million dollars. The number has increased significantly since that time. The budget for 2016-17 allocated a total of 138 million euros for financial support.

Namibia demanded $4 billion compensation. In 2015, the two countries started negotiating an agreement. Since 2015, eight rounds of talks have taken place but an agreement has not reached between the sides. One of the obstacles to the talks was naming the payment. The German government is against the use of the word "reparations". Currently, the sides hold discussions on the use of terms “reconciliation and peace”. In 2017, Namibia stated that it will launch a 30-billion-dollar lawsuit against Germany.

On 11 August 2020, following negotiations over a potential compensation agreement between Germany and Namibia, President Hage Geingob of Namibia stated that the German government's offer was "not acceptable", while German envoy Ruprecht Polenz said he was "still optimistic that a solution can be found."

More about: