In particular, the team wanted to mimic the makeup of plant cells, which contain aligned cellulose fibres that constrain their range of motion. They mixed cellulose fibres from wood pulp with acrylamide hydrogel, a jelly-like substance that expands when submerged in water. When extruded through a 3D printer nozzle, these fibres line up within the gel, meaning the printed object can only expand lengthways, not sideways.

By itself this property is fairly limited, but the team also developed a mathematical model for printing curved shapes from criss-crossed designs, using the fibre alignment to ensure the shapes bend in the exact way the team wanted. “Depending on how we actually print the material, we can encode bending, twisting and ruffling,” says Lewis.

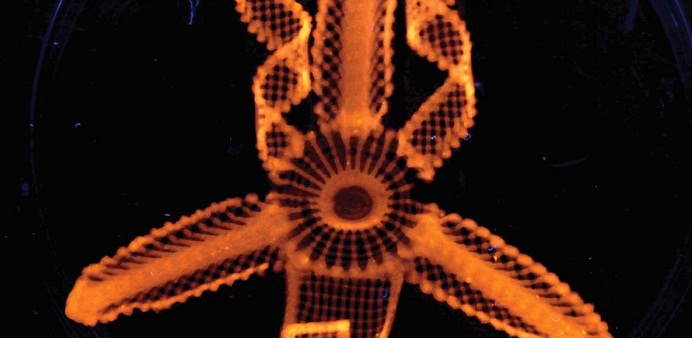

To test this out, the team printed two flower shapes that superficially look the same, but curl their five petals in different directions when exposed to water. They also copied the design of an orchid, with a flat shape that becomes a close approximation of the real thing once it bends and curls (pictured above). The team added a fluorescent dye to the gel, making the flower easier to see and giving it a pleasant glow.

Now the team is exploring potential applications for their technology, including tissue engineering that could ultimately grow new organs. “Right now most tissue culture is done in two dimensions, but most applications of these cells are in 3D,” Lewis says. In the future, a replacement for damaged tissue could be printed as a flat sheet and then turn itself into the required shape, she says.

More about:

-1741278702.jpg&h=190&w=280&zc=1&q=100)