Eighteen images of ships, scratched on the building’s walls by French prisoners of war in the mid-18th century, have been found by historical investigators carrying out conservation work at a National Trust property, Sissinghurst Castle, 13 miles south of Maidstone.

Together with 16 other previously known ship images at the site, it is the largest collection of pre-19th century prisoner-of-war art ever discovered in Britain. All 34 graffiti images are now being studied in detail.

Historians believe that originally there were up to 3,000 PoW drawings carved on Sissinghurst’s walls – and that hundreds are still hidden under early 20th century plaster, awaiting discovery.

The art was produced by French and other PoWs captured by Britain in the run-up to and during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). It was the first really major global war – with fighting taking place in Europe, North America, the Caribbean, South America, India, the Philippines and West Africa. In total, the conflict involved 17 different countries and other political entities and cost around 1.5 million lives – three times more than the only earlier truly global conflict, the War of the Austrian Succession, which had ended only eight years previously.

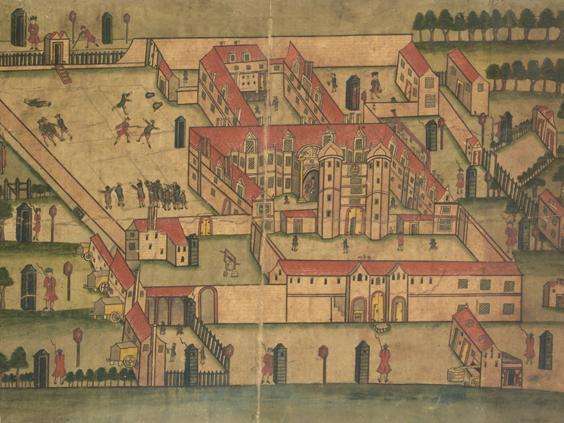

For more than 200 years nobody knew what this painting rep

resented. Then new research revealed it was the Seven Years’ War detention centre at Sissinghurst (National Trust/John Hammond)

The conflict brought death and suffering to troops and civilians alike – and prisoners of war were certainly not exempt.

Some 61,000 French and other enemy troops were held captive in a network of oppressive detention centres throughout Britain.

Many were kept incarcerated for between two and seven years. Thousands died from typhus and other diseases. Dozens were murdered by their guards. Across the Channel, thousands of British PoWs suffered in equally terrible French prison camps.

Of the 61,000 French and other prisoners (including Germans, Scandinavians and Italians) incarcerated in Britain, around 3,000 were kept in appallingly overcrowded conditions at Sissinghurst.

A guard shoots a prisoner of war who has come too close to the perimeter of the detention centre (National Trust/John Hammond)

These were the men who, to alleviate the emptiness and boredom of their imprisonment, scratched and chiselled vast numbers of ship images into the walls of the castle. The 34 engravings of ships, the majority of which have only been discovered over the past year, have now been recorded in detail by Britain’s leading historical graffiti expert, archaeologist Matthew Champion. His recording work has revealed the substantial variety of vessels in which the men had served.

A leading expert on 18th century ships, Dr Peter Goodwin, former curator of Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory, believes that some of the better preserved graffiti represent small privateers, fishing vessels and merchantmen. The privateers – mostly in the 55ft to 70ft range – would have had relatively small crews (probably no more than a dozen men each), while the merchant vessels (in the 60ft to 110ft range) may well have also functioned as privateers or as French troop transports.

Overall prisoner-of-war statistics for the Seven Years’ War, together with analysis of the ship types portrayed in the graffiti, suggest that the majority of the men at Sissinghurst were sailors (often fishermen and the crews of small privately owned and operated ‘privateer’ warships, acting on behalf of the French government).

In the 16th to 18th centuries, it was common practice to privatise warfare – with British, French and other governments licensing privateers (in effect, government-backed pirates) to attack and capture enemy shipping. In the Seven’ Years War just over 30 per cent of the 61,000 PoWs in Britain were from such vessels.

However, fishermen and the crews of ordinary merchant ships were also seized by the British – not as enemy combatants, but as part of a policy to harm the French economy and to capture men who might otherwise potentially be recruited or press-ganged into the French navy. Around 17 per cent of the 61,000 PoWs in Britain fell into that category.

Interestingly, only 8 per cent of the PoWs came from official French Royal Navy warships – a fact reflected in the Sissinghurst graffiti where it is likely none of the currently visible ship engravings portray really large warships of that kind.

As well as sailors, there were an estimated 27,000 French and other soldiers incarcerated as PoWs in Britain. On the whole, these were troops who were being transported by the French government by ship to the various overseas theatres of conflict.

It’s not known from which ships the Sissinghurst prisoners came, but key battles which provided large numbers of French POWs took place in August 1759 off the coast of southern Portugal (the Battle of Lagos) and in November 1759 off the coast of Brittany (the Battle of Quiberon Bay – known as the Trafalgar of the 18th century – a pivotal sea battle that helped determine the course of the war).

It is therefore conceivable that some of the prisoners at Sissinghurst came from major French warships captured in those two battles – the Temeraire, the Modeste and the Centaur, all captured in August 1759, and the Formidable, captured in November of that year.

In a sense, some of the French PoW graffiti (depicting ships captured by the Royal Navy) symbolise the emergence by 1759 of Britain as the world’s top naval power – a position it then maintained for almost 200 years. For the remainder of the 18th century, that year was known as the UK’s annus mirabilis.

The PoWs at Sissinghurst and the nine other major UK camps were, in part, guarded by local militiamen – not by regular soldiers. The militiamen were notorious for being much less disciplined and much more corrupt than regular troops. They were also often brutal.

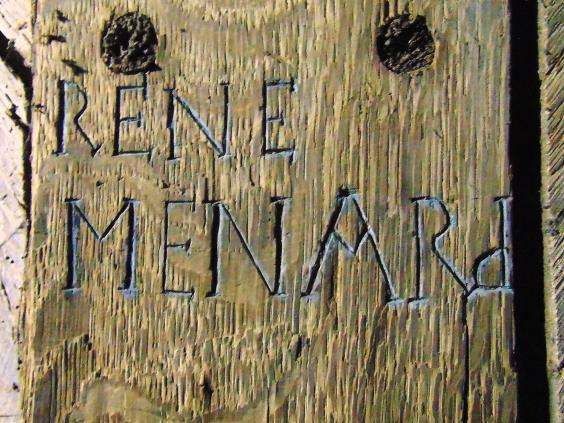

A carving thought to be the name of a prisoner

“The graffiti is of great importance because it adds to our understanding of who these prisoners were and perhaps even how they perceived their role in the war. In a sense, the images aren’t just pictures of ships but are also statements of communal identity,” said a leading expert on 18th century PoWs, Cambridge historian Dr Renaud Morieux, who is investigating Sissinghurst and the other Seven Years’ War PoW camps for a groundbreaking new book (The Society of Prisoners: War Captivity, Britain and France in the Eighteenth Century) due out early next year.

The men at Sissinghurst – including those who created the ship graffiti – seem to have led a fairly miserable existence.

Prisoners could be shot for not putting out their lights on time, for walking too close to the camp’s perimeter fence, and even for not instantly obeying instructions to collect clothes hung out to dry.

The guards also sometimes beat their captives with the blunt side of their sabres.

For the slightest infringements of regulations, the prisoners could have their food provision cut in half.

The guards also frequently confiscated the personal property of prisoners – and then sold the items back to other prisoners. It seems that the militiamen used the camp as an opportunity to bolster their meagre incomes.

The records also reveal that letters from the prisoners’ wives and families were often kept by the militiamen and not handed over.

All of this generated huge resentment on the part of the prisoners. There were escape attempts at Sissinghurst – and even petitions to the British Admiralty protesting against the harsh conditions. On one occasion, the PoWs protested against the lack of proper clothing provision by turning out on parade for their captors scantily clad or indeed stark naked. The furious militiamen retaliated to this naked Gallic insult by cutting the prisoners’ food provision as well as their supply of clothing.

Not only has the graffiti survived, but the letters withheld by the militiamen also still exist – along with a series of artefacts made by the PoWs.

Detailed analysis of those letters and other documents is currently being carried out by Dr Morieux and will be published in his book early next year.

The Independent

More about: art