Arcangel edited the clips to play a composition by Arnold Schoenberg, early 20th century pioneer of atonal music. “It was an experiment to see if cats could make atonal music go viral, whether cats could make this happen,” Arcangel says. “It was a very elaborate and complicated joke.”

The experiment worked, his video became popular, even appearing on blogs for cute animals as well as contemporary music mailing lists.

“Cats seem to be an eerily photogenic animal for video, they come across well on the silver screen,” jokes Arcangel. Without cats, a compilation of atonal music by a contemporary artist would have a niche audience, to say the least. But we all go nuts for watching animals perform human-like actions.

Cat memes are, of course, a very 21st century art form – if you can call them that when they’re not accompanied by difficult German compositions. But the human urge to make art about animals is almost as old as art itself.

A new exhibition at Turner Contemporary in Margate explores artists’ relationships with animals, from the very beginning up to the present day. The first known figurative drawing is of a deer: before this, for thousands of years, humans made imprints of their hands on cave walls. It is guessed that the first paint was probably animal blood.

In ancient civilisations, animals became symbolic, as we imbued them with meaning. Eight of the 12 signs of the Zodiac are animals. Animal figurines in ancient Egypt formed the basis for myths, that actually explored our own human psychology.

A bronze standing statuette of goddess Bastet from the Egyptian late period, 600BC-332BC, and taken from Sigmund Freud’s collection of Egyptian figures (Freud Museum London)

A cat-headed goddess, Bastet, represented the protectiveness of a mother figure as well as a merciless and violent avenger of the wronged, for instance. Not such good news for our furry friends: sadly, thousands of cats were offered as sacrifice to this goddess, their remains turned into fertiliser.

“[An] animal’s silence guarantees its separation from man,” wrote the critic John Berger in his essay “Why Look at Animals?” And yet, their silence also allows us to make them like us. Or to believe they are.

We think dogs are happy when they jump up and down. Horses lay their ears back before they bite but they cannot ell us how they feel, whether they like us. We anthropomorphise, or turn animals into metaphors about us.

This tendency can be seen in our interaction with pets and – yes – our obsession with cute animal videos online. But it also make its way into art, as shown in the Animals and Us exhibition.

Raqib Shaw’s glitzy and colourful work Monkey King Boudoir II shows a monkey army doing something awful to their monkey king. Human-like in their greed and destruction, they tear each other apart.

I Like America and America Likes Me is German artist Joseph Beuys’ famous film of his three days in an art gallery with a wild coyote. Coyotes appear in Native American folklore as tricksters. To Beuys they became the spirit of America. They stood for the power imbalance between indigenous, immigrant and minority people against white politicians.

The performance used the coyote as a metaphor for America at the time. The tension and uncertainty between the coyote and Beuys reflects his own ambivalence towards America, as well as representing the divisions in America over the Vietnam war.

For Tracey Emin, a fox represents the elusiveness of love. Her video, Love never wanted me, shows her attempts to befriend a fox, who appears and disappears, while she reads out a poem about love being too painful a risk for her to take. The video shows how a human watches an animal, and how an animal observes us: evasive, curious and distrustful.

But the humble beast can also be made to do another kind of work for humankind: they become our trophies, our status symbols, our entertainment, often wrenched from their natural habitat and forced to work, to perform, to please us, or to be consumed by us.

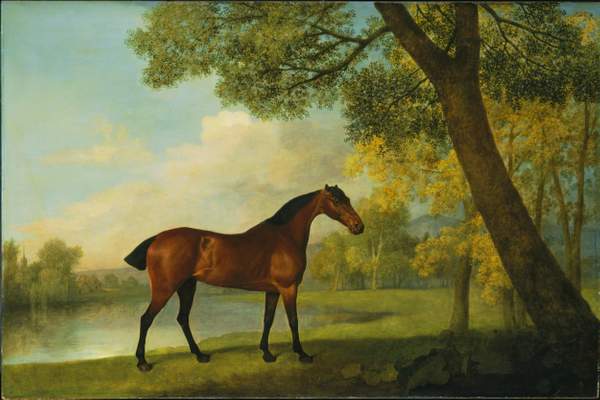

‘Bay Hunter by a Lake’ by George Stubbs,1787 (Tate)

Sketches by JMW Turner show working animals: oxen pulling a cart, donkeys and gun dogs. Animals here became status symbols like expensive cars or a private jet. George Stubbs’ painting Bay Hunter by a Lake shows a majestic and moody looking horse, ears slightly back, nostrils contracted. Only the rich could own such a creature.

Laura Ford’s sculpture A King’s Appetite is a large, crudely made giraffe, lying flat out with its ragged head on a cushion. It represents the first giraffe to come to Britain in 1827, as a gift from the Pasha of Egypt to our King. The poor thing was transported on the back of a camel across the desert, then shipped. It lasted a couple of years before dying in George IV’s menagerie at Windsor castle.

We have become increasingly disassociated from animals, as industrial farming makes them less real, no more than slabs of meat on a polystyrene tray. Animals required for food are processed like manufactured commodities.

Photographer Mishka Henner makes compilations from satellite images of industrial beef farms. Rivers of manure, urine and chemicals appear like vast lakes of blood in the Texan landscape. “These images reflect a blueprint and a horror that lie at the heart of the way we live,” Henner has said about his work.

Mishka Henner’s ‘Coronado Feeders, Dalhart, Texas’, 2012 (Mishka Henner)

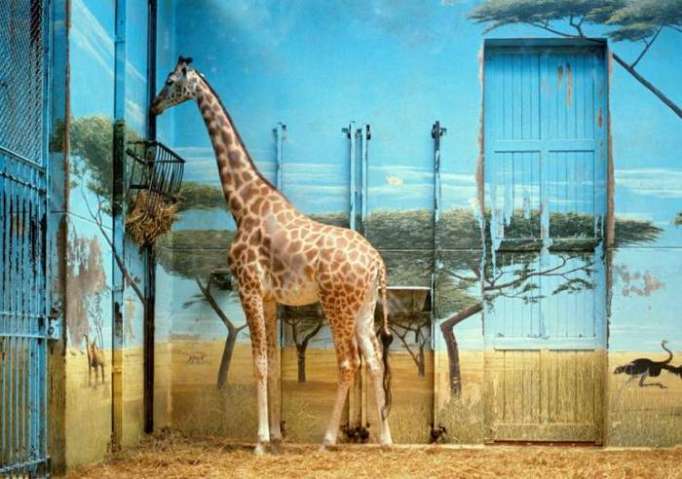

Candida Hofer’s mournful photographs of animals in zoos, meanwhile, reflect a heartbreaking ennui in once-wild animals captured for our benefit. A single giraffe faced towards the wall eats from his hay manger, the inside of his stable painted with garish scenes of an African landscape. Elephants are crammed into the zoo’s sturdy grey modernist stalls, their surroundings matching their gargantuan physiques.

These are animals marginalised, a bitter-sweet tourist attraction that reflects their gradual disappearance from our lives. And disappearing they are: since 1970, the animal population has declined by a staggering 38 per cent. It’s thought that up to 100,000 species of animals go extinct every year.

The great auk is a black and white bird like a penguin became extinct in the mid-19th century. It couldn’t fly, which made it easy to catch. Europeans prized its down for their cushions, which led to overhunting. Marcus Coates’ film shows him in the bird’s native habitat: Fogo Island in Canada.

He organises a committee with the mayor, to make a speech, Apology to the Great Auk. The mayor reads the speech out towards the sea, in front of a small audience, as he promises to protect future species.

In another artwork, Coates decided to flip things the other way, by becoming an animal. In Goshawk, he hangs half way up a Scots pine, inhabiting the position usually occupied by a Goshawk as it looks out for prey. In Stoat, he wears wooden stilts designed to make him move as awkwardly as a stoat does. He clatters along the road, permanently on the edge of falling.

It feels futile, of course, because we know he can’t actually feel like an animal. None of us truly can. For now, we project our fantasies onto them. We watch films of talking animals and give children stuffed bears. One in four of us have an animal in our house. With our pets, we hope they love us as we love them.

Tracey Emin’s ‘Docket in my Hand’, 2012 (Tracey Emin)

“I have lived with my cat Docket for 18 years now. I never knew I could love an animal so much, but it’s a joining of souls,” Tracey Emin has said of her relationship with her cat.

She may be right; research on animals has shown then to be more conscious than we might have believed. Horses remember your mood, elephants display empathy; a humpback whale rescued a seal from being attacked by killer whales. Emin’s cat might love her, with his particular kind of cat love. Perhaps he would make a miniature sculpture of her in bronze, as she has made of him, if he could.

The Independent

More about: art