Imagine that, when you were 12 years old, your family moved to the other side of the country. In your new school, you were bullied for the first time. When you reflect upon this period of your life today, do you see this as just one of many episodes in which things were going great, and then turned sour? Or do you see it as another example of a tough experience that had a happy ending – perhaps the bullying toughened you up, or led you to meet the person who became your lifelong buddy?

It may not seem as if the way you tell this story, even just to yourself, would shape who you are. But it turns out that how you interpret your life, and tell its story, has profound effects on what kind of person you become.

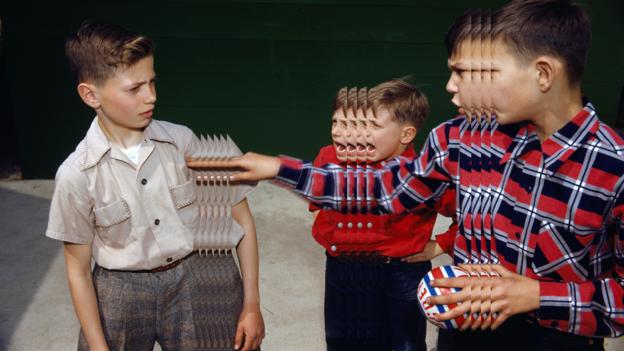

How you talk about the main events of your life can have profound effects on who you become (Credit: BBC/Getty Images)

In the mid-20th Century, the show This Is Your Life was a popular staple on British and US televisions. It involved celebrities and non-celebrities being presented with a red book that featured key events, pivotal turning points and memories from their lives. For the show, these life stories were compiled by researchers. But in reality each of us walks around with a version of the “red book” – one personally authored, often without us even realising it – in our mind.

These narratives exist whether we choose to give them much conscious attention or not. They lend meaning to our existence and provide the foundation for our sense of identity. You are your story. As a team led by Kate McLean at Western Washington University described it in their recent paper in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, “the stories we tell about ourselves reveal ourselves, construct ourselves, and sustain ourselves through time”.

The new research from McLean’s group is among the latest to explore the intriguing idea that – though we constantly revise and update them – these personal stories contain various stable elements that reveal something inherent about us. They reflect a fundamental aspect of our personality.

One of McLean’s collaborators, personality expert and pioneer in the field Dan P McAdams at Northwestern University, explained this in his seminal paper The Psychology of Life Stories: “People differ from each other with respect to their self-defining life stories in ways that are not unlike how they differ from each other on more conventional psychological characteristics such as traits.”

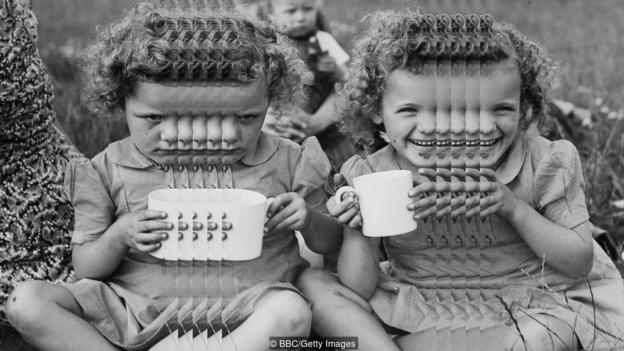

In the same way that people have different traits, they tell their life stories using different styles (Credit: BBC/Getty Images)

In the almost two decades since McAdams made that claim, evidence has accumulated to support the idea that, alongside our goals and values and character traits, our personal narratives reflect a stable aspect of our personalities. (McAdams labels these three aspects of the self the “Personological Trinity”).

Other work also has illustrated the significance of the idea of self-stories as part of personality, since the way we tell our personal stories turns out to have implications for our mental health and overall wellbeing. For instance, if you’re the kind of person who would remember the positives that came out of that (hypothetical) bullying episode at your new school, it’s also more likely that you enjoy a greater sense of wellbeing and satisfaction in life. Moreover, this raises the tantalising possibility that changing your self-authoring style and focus could be beneficial – indeed, helping people to re-interpret their personal stories in a more constructive light is the basis of what’s known as “narrative therapy”. The red book in your head is not the final edition. Modify your story as you tell it, and perhaps you can change the kind of person you are.

But what are the different styles of narrating our lives? When it comes to describing people’s character traits – the conventional way of thinking about personality – the most widely supported and researched theory in the field suggests that, from the thousands of trait terms in the English language, there can be distilled a “Big Five” (including extroversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism and so on) that capture the essence of each individual.

And, it seems, our life stories similarly have main features by which each of us can be defined. Research has measured a “dizzying” range of different aspects of people’s personal stories, including (and as first compiled by McLean’s collaborator Jonathan Adler): “agency, communion, valence, redemption, contamination, closure, coherence (at least three kinds), exploratory processing, growth goals, integrative and intrinsic memories, positive and negative meaning-making, elaboration, sophistication, accommodative processing, differentiated processing, ending valence, affective processing, intimacy, foreshadowing, complexity”.

When we tell our life stories we tend to emphasise either the negative or positive more, which says something about who we are (Credit: BBC/Getty Images)

To distill the most meaningful life story features from this list, McLean and her team conducted three studies involving nearly 1,000 volunteers. Each provided stories of particular episodes from their lives or an overarching narrative summarising their entire life story. Based on a thorough analysis and coding of the narratives they produced, McLean and her colleagues believe there is a “Big Three” of key features that represent the characteristic way we tell our life stories.

The first is “Motivational and Affective Themes”, which look at how much autonomy and connection with others the narrator expresses, as well as how positive or negative the stories are overall, and whether they are dominated by good situations turning sour (seeing that bullying episode as ruining things), or bad situations working out well in the end (like when the bullying led to positive outcomes). The second is “Autobiographical Reasoning”, which is how much we reflect on the experiences in our stories, find meaning in what’s happened, and discern links between key events and ways we have and haven’t changed. Finally, there is “Structure”, or how much our stories make sense, in terms of their timeline, facts and context.

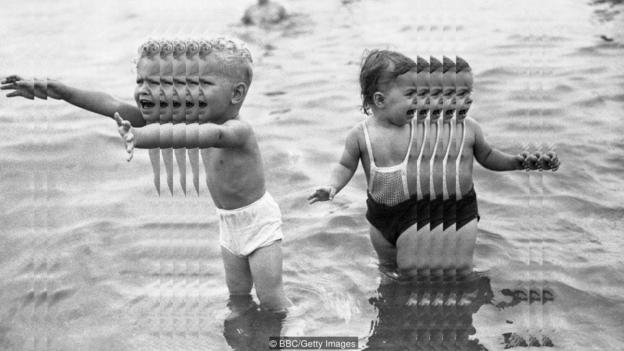

How much our stories have a structure also gives an insight into the type of personality we have (Credit: BBC/Getty Images)

For our personal narratives to be akin to an aspect of personality, they need to show a degree of meaningful stability over time (similar to the stability of our character traits).

Recent research suggests this is indeed the case. For instance, Robyn Fivush at Emory University and her colleagues asked nearly 100 adult volunteers to tell their life stories in an interview. They caught up with them again four years later, at which point they invited them to tell their life stories once again.

Crucially, the researchers found that the “coherence” of their volunteers’ stories showed stability across the duration of the study (a feature similar to the “Structure” characteristic identified by McLean’s team). “The ways in which we tell autobiographical narratives reflect a stable aspect of individual differences,” Fivush and her team concluded.

This latest result adds to similar recent findings, such as that the event content of our personal stories acquires an element of stability from mid-adolescence, becoming increasingly consistent as we get older, and that the relative frequency of redemptive and contaminating sequences in young people’s stories shows a degree of stability over several years (that is, while the frequency of these stories changed over time, the participants who had relatively more of these sequences at the first telling also tended to have more at the second telling three years later).

The event content of our personal stories becomes increasingly consistent as we get older (Credit: BBC/Getty Images)

This notion that our life stories reflect a stable and important aspect of our personalities may have important consequences. A few years ago, Jonathan Adler at the Franklin W Olin College of Engineering and his collaborators, including Iliane Houle at University of Quebec at Montreal, reviewed 30 previous investigations into life stories and found that several aspects are linked to wellbeing.

People who tell more positive stories and stories with more elements of redemption (for example, that time that you lost your job, but ended up switching career paths into something you enjoy much more) tend to enjoy greater wellbeing, at least based on research with Western samples, in terms of more life satisfaction and better mental health. So do people whose stories express a greater sense of being a protagonist in the events of their life and having more meaningful communion with others. For example, the episodes they remember frequently involve loved ones and close friends, such as that hilarious hen night in Brighton, or shared hobbies, like the time they and their cousin went to cooking classes together. Engaging in more autobiographical reasoning and having greater structure to one’s life story also correlates with greater wellbeing.

Conversely, telling stories with more “contamination”, less autonomy and communion correlates with lower wellbeing.

Furthermore, there is some limited evidence that increases in the positive features of one’s life story precede subsequent beneficial consequences for wellbeing, rather than simply reflecting life going better – although Adler and his colleagues caution that more long-term research is needed to establish causality.

There is evidence that increases in the positive features of one’s life story precede benefits for wellbeing (Credit: BBC/Getty Images)

Does this mean that if you can revise your life story, such as by considering the positives that came out of negative experiences, you might be able to develop a more robust and healthy personality?

The idea is not entirely far-fetched. Consider one recent study in which student volunteers were asked to write narratives so that they featured more redemptive sequences (such as by considering “one time that a failure has changed you for the better”).

Compared with control participants who weren’t prompted in this way, those encouraged to feature more redemptive sequences subsequently showed greater goal persistence, even several weeks later, saying that they tended to finish whatever they started. “Not only do these findings provide evidence that personal narratives can be shaped,” the researchers concluded, “they also suggest that shifting the ways people think and talk about important life events can influence their lives moving forward.”

As philosophers have long argued, there is a sense in which we construct our own realities. The world is what we make of it. Usually this liberating perspective is applied by psychotherapists to help people deal with specific fears and anxieties. Life story research suggests a similar principle may be applicable at a grander level, in the very way that we author our own lives, therefore shaping who we are. Now that’s a tale worth sharing.

BBC Future

More about: life