Has art forgotten how to frighten us? In times past, artists understood fear and exploited it as among the most potent emotional levers that a painting or sculpture could pull. Medieval and Renaissance religious artists were especially tuned in to its appalling power. Terrifying visions of what eternal discomforts await in the afterlife should parishioners fail to live piously in this world (typically positioned near the exit to a church in order to leave an indelible impression), served a clear, if ghastly, purpose: to scare the congregation straight.

The last thing worshippers witness on exiting the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy, for example, is a ghoulish glimpse into a sump of damned souls as they are sucked into the fiery maw of hell as imagined by the late-13th Century Florentine master, Giotto di Bondone. Giotto’s deeply disquieting Day of Judgement (which broadcasts above the rear door of the chapel on a split-screen fresco that simultaneously portrays the matriculation into heaven of the righteous and redeemed) may not be subtle, but it is effective. “The blessed arrange themselves in neat rows on the right hand of Christ,” as one scholar describes the scene, “while the damned stream in twisted shapes, bodies elongated, flowing downward… attacked by demons who stab, burn, and pull them apart”.

Giotto’s fresco cycle at the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua includes a terrifying Day of Judgement, placed above the exit (Credit: Creative Commons)

However fear-inducing the imaginations of Giotto, say, or Hieronymus Bosch, the faces depicted in their paintings rarely resonate convincingly with an inner turmoil of anguish. Adding to the eeriness of the gruesome gymnastics Bosch choreographs in the Hell panel of his Garden of Earthly Delights is the incongruous placidity of those being pecked or flayed. It would fall to ensuing generations of artists to tackle the challenge of actually chiselling a compelling semblance of foreboding into the physiognomies of their subjects.

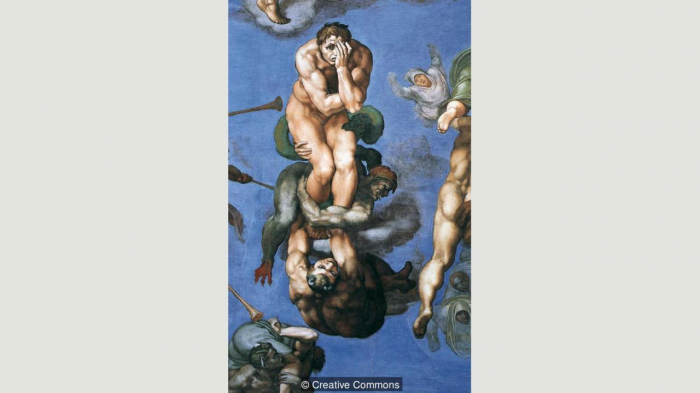

Michelangelo’s Last Judgement fresco covers the entire altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City; on the right, the souls of the damned descend to hell

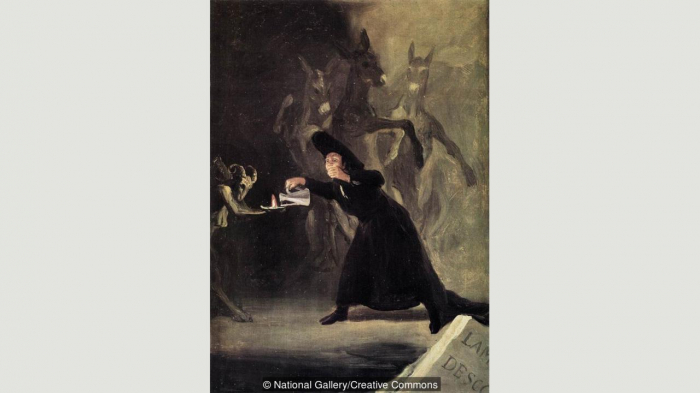

From the damned soul who slowly sinks alone to eternal torture in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco of The Last Judgement (his physique tugged and wrenched by an entwined trio of devilish tormentors) to the aghast visage of Francisco Goya’s The Bewitched Man (1798); from Swiss artist Henri Fuseli’s bloodless likeness of a petrified Lady Macbeth to Edvard Munch’s iconic personification of existential dread, The Scream, the history of art has ceaselessly auditioned archetypes of enduring angst.

The Bewitched Man by Goya depicts a scene from a play in which the protagonist, Don Claudio, believes he is bewitched and that his life depends on keeping a lamp alight

Two lesser-known works created exactly a century ago show how the quest to find the true face of fear continued into the 20th Century. Still a student at the Slade School of Fine Art in London (having taken a hiatus from her studies in 1917 after being traumatised by the sight of an explosion at a munitions factory in Essex during the first World War), the British artist Winifred Knights was awarded a prestigious Rome Scholarship for her dramatic take on a scene inspired by the biblical flood. Amid a frenzy of scampering figures desperate to reach higher ground as Noah’s ark slips by unnoticed in the distance, it is a self-portrait of the artist herself – just off-centre in the foreground of the work, her limbs and psyche ripped in two directions – that crystallises persuasively the ferocity of fear as it continued to trouble the consciousness of Europe, still recovering from the horrors of war.

The Deluge (1920) by Winifred Knights depicts an apocalyptic flood in which figures flee to higher ground while Noah’s ark glides away in the distance

At almost the same moment that a panel of judges (including John Singer Sargent) was praising Knights’ work, the Spanish Expressionist José Gutiérrez Solana found himself at work on a rather quieter, though no less psychologically complex, double portrait that explores the same emotion if from a somewhat subtler angle. Though there is no furious scurrying for diluvial survival in Solana’s portrayal of a pair of off-duty jesters in The Clowns, a soulful foreboding haunts the carnivalesque complexion of the mime on the right.

Solana’s 1920 painting, The Clowns, conveys a sense of dread through nuanced facial expressions (Credit: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía)

Research has shown that fear is tough to fake, involving as it does more muscles in the top of the face than other emotions, and one connects instinctively with the authenticity of anguish that rumples the brow of the horn-holding clown who looks blankly askance in abject dread of some undisclosed figure or force beyond the frame to our right. Though his depiction doubtless owes something to the serial Pierrot portraits for which his fellow Spaniard, Picasso, was well-known, Solana conjures a genuine fearfulness that is impossible to counterfeit.

Hirst’s For the Love of God, a skull made of diamonds, was displayed in Doha, Qatar, in 2013 (Credit: Niccolo Guasti/Getty Images)

But what about today? Is there a discernible legacy in contemporary art of such incitement to fear as one finds in Giotto or Bosch, or of the perennial ambition – from Michelangelo to Munch – to forge the quintessential face of fear? Damien Hirst’s notorious diamond-encrusted skull, For the Love of God (2007), springs to mind as a notable modern reinvention of the memento mori tradition in art history, which customarily features skulls and skeletons not so much intended to make you merely ‘remember you must die’ (the meaning of the Latin phrase) but scare you witless by death’s imminence. Hirst’s grimacing curio, comprised of more than 8,600 flawless diamonds, does not so much excite fear, however, as bemusement and exasperation at the outlandish cost of constructing such a gaudy gewgaw, let alone purchasing it. The asking price was £50 million. For the love of God, indeed.

So concerned with ceaselessly skirmishing over whether what they do is or isn’t art, many recent artists, one begins to sense, have simply lost touch with the full palette of emotions with which art is capable of being inflected, with the pigment of fear having arguably dried up the most. While it’s true that Hirst’s peers, the British brothers Jake and Dinos Chapman, routinely flirt with fear as a potential aesthetic element in a body of work that embraces creepy haunted-house mannequins to childish defacements of appropriated images from Francisco Goya’s chilling The Disasters of War series, their meta mockeries of the macabre are, perhaps unintentionally, less scary than silly.

Their work Hell is not about the Holocaust, say the Chapman brothers: “It’s the absolute inverse of that, it’s the Nazis who are being subjected to industrial genocide”

In the Chapmans’ own portrayal of Hell (for a controversial installation by that title unveiled in 2000), tens of thousands of toy soldiers were recast as a barbaric battalion of demonic Nazis and their victims – an outrageous orgy of violence that occupied nine large vitrines arranged into a huge swastika. A labour of loathing, the work took the siblings 24 months to construct. But to what end? The Chapmans’ playdate with Hitler landed more as a fatuous joke than a fearful jolt – even, it would seem, to the brothers themselves. “When it caught fire,” Jake confessed, after learning that the sprawling work had been destroyed in a devastating storage warehouse blaze in 2004, “we just laughed. Two years to make, two minutes to burn.”

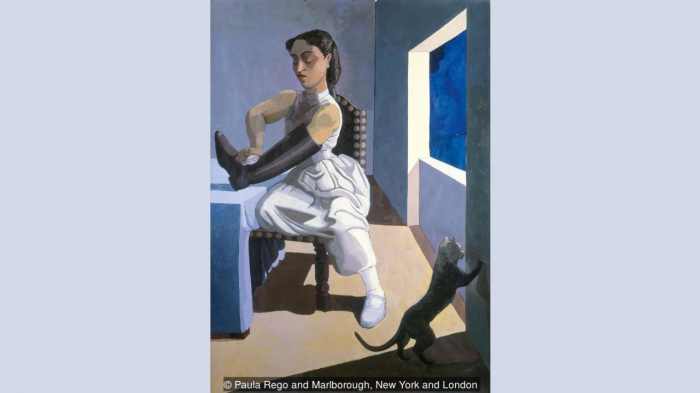

Rego’s painting The Policeman’s Daughter (1987) shows a woman angrily polishing a boot; it was part of a series exploring dysfunctional family relationships

So where has fear gone in visual culture? The celebrated Portuguese painter Paula Rego is often cited in the context of terror and fright. A recent academic article by the art historian Leonor de Oliveira entitled To Give Fear a Face: Memory and Fear in Paula Rego’s Work eloquently argues that Rego’s recurring motifs are indebted to the British art critic Herbert Read’s famous concept of “the geometry of fear”, coined by Read to describe the work of post-war sculptors whom, he clarified, had forged an “iconography of despair”. But to my eye, the formidable figures we encounter in Rego’s work – from The Policeman’s Daughter (1987) who portentously polishes a jackboot to her portrait of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre in the menacing red room – invariably defy fear rather than embody it.

The word ‘fear’ is frequently invoked to characterise too what’s elicited by the recent work of Swedish video artist and sculptor Nathalie Djurberg, whose uncanny and carnivalesque installations (often conceived in collaboration with the sound artist Hans Berg) invite visitors into a repressed realm of engrossing grotesqueries. But the lasting impression of displays such as One Last Trip to the Underworld (2019), comprised of darkly comic sculptures of fantastical flora and fauna that flicker freakishly into life by the light of looping films, is one of quizzicality and wonder more than tension and terror.

Perhaps contemporary art, like contemporary poetry, has contented itself in deferring roles it once performed to other shapes of culture that seem better suited to the task. Just as we rarely turn now to poets to tell us epics – a job more alluringly tackled by novelists and filmmakers – we’ve ceased looking, too, to artists to frighten us into a new consciousness. This year alone is due to witness the reboot of a string of seemingly inexhaustible horror film franchises, from Saw to Friday the 13th to Halloween. It’s well established that coming face to face with fear triggers a feel-good dopamine rush, and there’s even evidence that it can boost one’s immune system. If contemporary art sometimes struggles to connect with wider audiences, perhaps the addictive drug of fear is among the cures. Perhaps it’s time that artists rediscover the fear.

BBC

More about: images