Much of the world is having to learn fast about self-isolation. What tips can we glean from those who do it for a living?

In 2017, I tried to live like an astronaut. I didn’t float around in weightlessness, conduct any ground-breaking experiments or see the Earth from space. But I did spend two days confined to my apartment, where I worked, worked out, and limited my meals to freeze dried food from a pouch. It was an attempt to explore the effects of living in isolation from society and confined in the same place 24 hours a day, like astronauts do aboard the International Space Station, or may one day do on Mars.

Fast-forward to 2020. Millions of us are socially distancing around the globe in an attempt to slow the spread of coronavirus and no longer have to imagine what it’s like to spend the vast majority of the day in our homes.

As we grapple with our new routines, what advice can we glean from people who have already spent months in isolation? To find out, we caught up with two Nasa experts. The first is Kjell Lindgren, an astronaut who spent 141 days in space aboard the International Space Station (ISS) in 2015 with five crewmates. The second is Jocelyn Dunn, a human performance engineer who spent eight months living inside a dome habitat with five fellow volunteers as part of a Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (Hi-Seas) mission in 2014 and 2015. Here’s what they suggest.

Stay busy and make a schedule

On the ISS, astronauts’ days are scheduled down to five-minute increments with time for experiments, maintenance, conference calls, meals, working out and more. But even at home, Lindgren says it’s helpful to stay busy with meaningful work, even if it’s not your usual gig. “If you’re able to work from home it’s a gift,” he says. “Many people don’t have that opportunity. But finding some other meaningful work will help the time go fast. It is one of the blessings of being in the space station. The work can make six or nine months go very quickly.”

Lindgren, who is currently socially distancing at home with his wife and three children, says he talks to his kids weekly about what they want to accomplish and make sure to carve time out for it in addition to their regular schoolwork.

Dunn suggests breaking the day into parts with transitions like working out or going for a walk. At Hi-Seas, the crew would end the workday and transition into leisure time via a group work out. “When you work from home it’s easy to end up constantly working and never breaking,” she says.

In her forthcoming research Dunn and her colleagues also looked at how different crews on four, eight and 12-month missions spent their time and self-organised in the habitat, which included less than 1,500 sq ft (139 sq m) of living space. The results suggest that given autonomy, most people spent about the same amount of time on different activities.

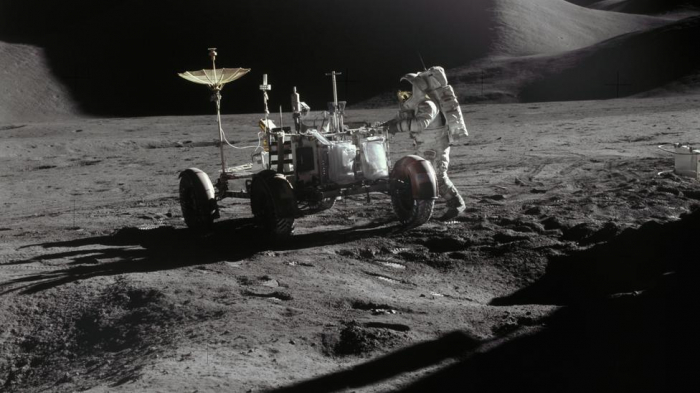

Astronauts serving on the ISS have a daily work and breaks schedule filled down to the last five minutes, helping give them purpose (Credit: Nasa/Getty Images)

In the habitat, participants spent about seven to eight hours on sleep, three to four hours on leisure activities, three to four hours on personal projects, an hour and a half working out, two hours on meals and half an hour on personal hygiene (which is low because shower time was extremely limited to simulate what life would be like on Mars). The rest of the time was spent on work.

Don’t dwell on the negative and forgive yourself for making mistakes

Lindgren recalls spending three hours fixing an exercise machine on Expedition 44/45. He got all the way to the end and realised the bracket he was left with didn’t fit. It turned out he had installed something that was intended for the left side on the right side of the machine and had to undo and redo all his work.

“I was really down on myself and folks on the ground gave me great advice. They asked for feedback on how to make the instructions clearer so that everyone could get something from my mistake,” he says. “They told me not to feel bad about it and move on, otherwise it would compromise my ability to do other things. That attitude served us well on the space station and I think it’ll serve us well here too.”

So, if you forget to buy toilet paper at the store or burn dinner, don’t sweat it, he says.

Communicate expectations to your crew

It’s important to manage expectations, both your own and those of your crew or the people you are living with, says Lindgren. And to regularly talk about what those expectations are.

In the Hi-Seas habitat, Dunn’s crew had a schedule for splitting shared household duties. They also set aside time each Sunday to debrief how the previous week had gone.

“We would take an hour to talk about the last week, reflect on things that went well, things that didn’t go so well and look at any challenges coming up in the next week. We considered it a safe place to bring up any frustrations we had,” she says.

Do fun things with your crew but also spend time by yourself

“Like our homes are now, the space station was our lab but also our home. So we had to find ways to have fun together. But it’s also important to read your team. Sometimes people need time alone to decompress,” says Lindgren.

On the Russian segment of his mission, the crew ended their work week with a group dinner. On the US segment, they had movie nights. “We would bring little treats to those," says Lindgren. "On the weekend we spent time coming up with games we could only do in weightlessness. That was a lot of fun and some of my fondest memories.”

On Earth, Lindgren’s family tries to schedule in social activities like a weekly TV show. “Anything that’s different from work that you can look forward to like staying in touch with loved ones over video conferencing – can be really helpful.”

Former Nasa astronaut Scott Kelly, who spent a year on the ISS, told the New York Times that he also made sure to make time for fun activities while on the space station – even if he was hurtling far above the Earth. That included watching all of Game of Thrones – twice.

When on a mission, the only way to go outside is suited up for a spacewalk – hardly a recipe for relaxation (Credit: Nasa/Getty Images)

For those finding themselves spending more time than they ever expected to with the people they live, Dunn reminds us to schedule alone time too. “One of the main takeaways from Hi-Seas was the importance of scheduling alone time in a confined situation. It’s fine to say I need 30 minutes on my own to do some mediation or journaling or just not have to talk to someone.”

Work out

It’s easy to motivate yourself to work out when your ability to walk when you return to Earth is on the line. But there are still lessons we can learn from the space station as we distance ourselves at home.

“We had two hours a day to work out, it was carved out into our schedule and expected that we were going to do it. That made it as easy as you could ask for,” says Lindgren.

Still, Lindgren, who’s now doing a group workout with fellow astronauts once a week over video chat, says we can make it easier for ourselves on Earth by removing as many barriers as possible. For example, schedule a specific time to work out, queue an internet workout onto your computer in advance, and prep any gear or clothes you need in advance.

Waking heart rate is a good indicator of biological and perceived stress

“Exercise is critically important,” he says. “Especially when we have this underlying stress because of the current situation, exercise provides a physical and psychological release.”

Speaking of stress, track your levels

As part of her research, Dunn tracked her crew’s stress levels during their eight-month stay in isolation and the stress levels of crews who were isolated for a year. Though the timing varied depending on the individual, participants tended to follow a similar pattern.

Everyone started with high biological stress levels but low perceived levels, which likely reflected their initial excitement of entering the dome. But from about six months on, both their biological and self-perceived stress levels were higher. Around the same time, people also started changing their sleep routines to avoid each other. Early birds started getting up earlier than before and night owls stayed up even later.

Dunn’s research in the habitat also proves that waking heart rate is a good indicator of biological and perceived stress. While a lot of wrist wearables can track your waking heart rate over time, Dunn says you don’t really need a high-tech device. Instead you can check in with yourself when you wake up and feel if your heart is racing.

Former Nasa astronaut Scott Kelly has said he found it vital to make time for fun, trivial activities (Credit: Nasa/Getty)

“The reason is the way your circadian rhythms work – melatonin makes you go to sleep and stress hormones wake you up. So if you already have higher stress hormones from confinement stress or other factors, a high waking heart rate represents your overall chronic stress level,” she says. If your waking heart rate increases over time, your coping strategies might need to be improved.

Expect conflict to happen

It was also around the six-month mark on Dunn’s mission that people started getting more confrontational and more likely to air their frustrations. Researchers call this the “third quarter phenomenon”, when people completing missions in challenging conditions, like astronauts, report a drop in morale.

“The third quarter phenomenon can start around the halfway point,” says Dunn, “People begin to feel there isn’t really an end in sight and the novelty of everything is gone. You might need to find some intrinsic or extrinsic motivation to keep you on good behavior and on better terms with the people you live with.”

She says that people tend to isolate themselves further in the third quarter too, which perpetuates their low mood. So it might be critical to keep those regular check-ins with friends and family, even if you no longer feel like it.

Interestingly, when Dunn compared the data from her own mission to that of the 12-month crew, the same issues appeared at around six months. An increase in conflict occurred in the third quarter in each instance, but there might also be something about six months of living together that makes people get on each other’s nerves.

“People might start off on their best behavior but after a few months they start to slide into their worst habits,” she says. When conflict arises, Dunn suggests refocusing on your own habits and modelling good behavior.

Kjell Lindgren (left) says mealtimes were an important time to reconnect with other crew members on the ISS (Credit: Nasa/Getty Images)

Though people are trying to predict when our need to socially distance might end, no one knows for sure how long it will last. So it’s hard to predict when our individual frustrations might surface. While six months might feel like “the third quarter” to some, two weeks might feel like “the third quarter” to others. It’s clearly a matter of expectation.

Perhaps that’s why we should mentally prepare for the long haul

“The most important difference between our experience and what is going on globally today is that we volunteered for our mission,” says Lindgren. “We knew what we were getting into and had the opportunity to prepare for it. Unfortunately, our communities have been thrown into this without much preparation so they’re having to learn to deal with the stress on the fly.”

Astronauts also know how long their missions will last, and any changes can be hard to cope with.

“When you build a mental model of when you launch and come back, changes to your launch or return dates are challenging,” Lindgren says. “I tried not to set a countdown timer so that if something changed, I wasn’t emotionally invested in the schedule.”

Lindgren suggests it might be smart to mentally prepare for the long haul and be pleasantly surprised by any reduction of restrictions. “It’s not as hard on you as the other way around.”

Remind yourself of the big picture

Our mission on Earth comes down to the health and safety of your loved ones and the community at large, says Lindgren. “If you think about working together to solve a crisis rather than be at odds with one another, the benefits are spectacular.”

He says that means we have to prioritise self-care, or doing things that prepare us to accomplish things as though we’re on a mission, like getting exercise and sleeping and eating well. This can help the people we’re home with but also the community at large.

“It would pay huge dividends if we look at this crisis as a united group rather than as individuals. Within our households we’re all crew mates, but we’re also crewmates within our communities, countries and the global community.”

So, if you have two packs of toilet paper, and see somebody scrambling for one at the market, give them one, he suggests. “Little expressions of love like that can go a long way.”

BBC Future

More about: astronaut