The fondness of artists for bringing to canvas Shakespeare’s dramatic – and tragic – heroes, his lustful lovers and truth-telling fools, means that the number of Shakespeare-related paintings out there is a bit daunting. But without (much) further ado, we’ve chosen a selection of paintings to highlight, with the stories behind them, to celebrate Shakespeare’s 453rd birthday.

Painting up a storm: the greatest tragedy

King Lear in the Storm 1767 (Photo credit: National Galleries of Scotland)

John Runciman (1744–1768)

The play that caused George Bernard Shaw to claim ‘No man will ever write a better tragedy… ’, King Lear is arguably Shakespeare’s greatest play. In this painting, John Runciman has placed Lear, raging against his unfaithful daughters, not on a heath, but by the sea, dramatising a physical stormy tempestuousness to accompany that taking place in Lear’s mind.

The painting is interesting because it’s a representation of Shakespeare’s original text at a time when a very different script was being used on stage. The version of King Lear altered by Nahum Tate was popular from around the 1680s, and, among other changes, Tate created a happy ending, with Cordelia on the throne and the strength of the monarchy restored. In the 1700s, productions began drifting back towards the original script, but the character of the Fool was still kept off the stage until 1838. By grouping together this particular set of characters – Lear, Edgar, Kent and, most importantly, the Fool – Runciman demonstrates his commitment to Shakespeare’s text, as originally written.

On a lighter note: the comedies

There are notably fewer famous artworks representing Shakespeare’s comedies: apparently painting a group wedding was less appealing than a good storm.

However, you can still search for any of the comedies on Art UK and find scenes from them brought to life in oil. You can, for example, see Hero fainting as she is accused by her fiancée Claudio of having a lover in Much Ado About Nothing or Aemilia being rescued from the shipwreck at the beginning of The Comedy of Errors.

'As You Like It' (3 panels) 1872–1873, (Photo credit: Walker Art Gallery)

Arthur Hughes (1832–1915)

These three panels, depicting scenes from As You Like It, are an example of the Pre-Raphaelite predilection for painting Shakespearean scenes. But they have another interesting dimension: their representation of Shakespeare's genderbending.

As stated by the home of this painting, the Walker Art Gallery: ‘Scenes from As You Like It were particularly interesting to artists due to the subversive reputation of the play, with its central themes of cross-dressing, entangled relationships and same-sex desire. In As You Like It the intelligent and beautiful Rosalind disguises herself as Ganymede and sets up home with her kind-hearted cousin, Celia… When Rosalind adopts the male dress her whole personality seems to transform and become more masculine, decisive and dominant. This provokes questions about the fluid nature of both gender and sexual desire.’

The problem play and John Everett Millais

‘She only said, "My life is dreary –

He cometh not" she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary –

I would that I were dead.’ – Mariana, by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Millais’ Ophelia is one of the best-known Shakespearean paintings (and one of the most-visited works at Tate Britain). The tortured character of Ophelia was almost matched by Millais’ tortured model Elizabeth Siddal, who had to lie in a bathtub for hours for him to capture the image of her floating downstream.

Slightly less well-known is Millais’ capturing of another tragic figure: Mariana. Measure for Measure is one of Shakespeare’s ‘problem plays’, neither fully tragic or comic, and while no character emerges from the story wholly untainted, Mariana is particularly hard done by. She is initially betrothed to the cold-hearted Angelo – who refuses to marry her when her dowry is lost at sea – and remains in love with him five years later. Through the play’s machinations, she agrees to take part in a ‘bed trick’ and sleeps with Angelo, who believes her to be the nun Isabella. Ultimately, Mariana gets what she wants and is married to Angelo – but it is hardly the set-up for a loving union, and she has to plead for his life when his duplicity is revealed.

In Millais’ painting, inspired by both the play and Tennyson’s poem, Mariana is waiting, frozen permanently in oils. Millais has her stretching out her back, stiff from needlework, impatient, looking world-weary and utterly tired of the hand she has been dealt.

Mariana 1851, (Photo credit: Tate)

John Everett Millais (1829–1896)

The otherworldly and Henry Fuseli

‘Infirm of purpose!

Give me the daggers.’ – Lady Macbeth, Macbeth

Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers ?exhibited 1812, (Photo credit: Tate)

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825)

Fuseli made numerous paintings based on Shakespeare’s plays – perhaps the most famous is his depiction of the witches from Macbeth. But this painting is one of the strangest: Macbeth and Lady Macbeth are rendered almost as wraiths, as somehow inhuman. The look of horror on Macbeth’s face, having just murdered King Duncan, is matched by the steely determination on his wife’s. The sense of having done something so terrible, that cannot be undone, is deeply unnerving. At a time when many artists were creating theatre-like representations of Shakespeare’s scenes, Fuseli’s paintings stand out for their imagination.

The description from Tate puts it well: ‘Fuseli created brilliantly imaginative renderings of the plays that blend icy precision and malevolent fantasy’.

All the world's a stage: Shakespearean actors in art

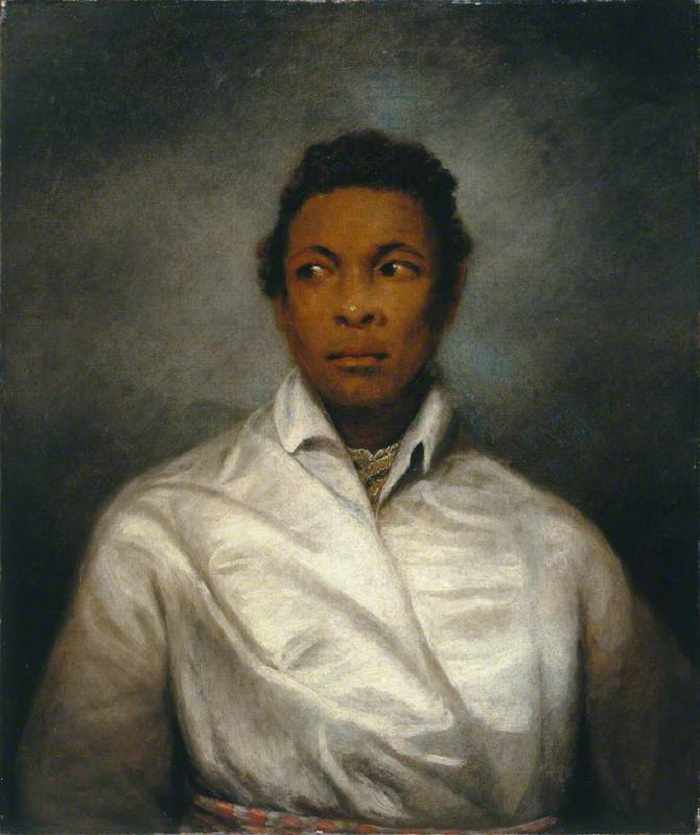

Othello, the Moor of Venice 1826, (Photo credit: Manchester Art Gallery)

James Northcote (1746–1831)

This powerful portrait depicts the nineteenth-century actor Ira Aldridge as Othello. Aldridge was the first black actor to play Othello in Britain, the first black manager of a theatre in Britain and one of the first black Shakespearean actors, full stop: a remarkable story in itself, recently brought to the stage in the play Red Velvet.

Aldridge was actually American, born in New York in 1807, but left the United States when persistent discrimination meant he was unable to work. Despite scepticism on his arrival in Britain, he went on to achieve fame across Europe, performed in Russia for Tsar Alexander II, and was considered a hero of the anti-slavery movement by the time of his death.

The Apotheosis of Garrick c.1782, (Photo credit: Royal Shakespeare Company Collection)

George Carter (1737–1795)

To put it mildly, there are a lot of paintings of David Garrick. Through his role as manager of the Drury Lane Theatre he was pivotal in re-popularising Shakespeare in the 1700s, and was himself a great actor, playing Richard III and King Lear to great acclaim. One of the most famous images is Hogarth’s painting of him playing Richard III, violently woken from a dream in which the ghosts of the people he’s murdered come to haunt him.

The above painting by George Carter shows Garrick being raised up to Mount Olympus, where he is greeted (presumably favourably) by Shakespeare himself, and the Muses of Comedy and Tragedy. Waving him off on his way to the afterlife are actors, in character, known for appearing with him in Shakespeare plays: a fitting end for the man who made Shakespeare beloved by Britain once again.

The Globe Theatre, with the Thames and St Paul's Cathedral 1981, (Photo credit: Shakespeare Birthplace Trust)

Arthur Keene (b.1930)

Molly Tresadern is Art UK Content Creator and Marketer.

The original article was publsihed on artuk.org.

More about: #Shakespeare #art