They revolted against war and haircuts, invented new art forms under the influence of psychedelic substances, and imagined art and life as inseparable in a future that would transcend the trappings of the West. They were the hippies. These flower children's vision of a free-love utopia was naive but hopeful, though ultimately disappointing.

The Black Panthers, Chicano activists and women fighting for civil rights also made their mark on the aesthetics and arts of the US counterculture, but their movements were written into history as political. While the hippies have been largely understood as a cultural movement, often infantilised and satirised, they were also highly political. Of course, the truth was more complicated than written history in a contentious landscape fraught with explosive conflict and fantastic creativity.

In his 2015 exhibition – Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota – curator Andrew Blauvelt aimed to show how, invigorated by energy from the prosperous post-war years, the counterculture movements surrounding the hippies set the stage for postmodernity. The 1960s and early 70s marked the peak, and ultimately the failure, of the modern dream of a world without pain and suffering. The years that followed ushered in a new era defined by neoliberalism and global capitalism.

The exhibition Hippie Modernism at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis included a van of the sort hippies often used (Credit: Photo by Greg Beckel, courtesy Walker Art Center)

“The history of modern art, architecture and design took a different path during this period,” Blauvelt tells BBC Culture, “suggesting an alternate history of modernism in the late 20th Century, one that is re-emerging today because, in part, we face the same social, political, economic, and environmental struggles as then, which never really went away.”

Many of the hippies of the 1960s became more conservative as they aged – as symbolised by the TV added to the van (Credit: Photo by Greg Beckel, courtesy Walker Art Center)

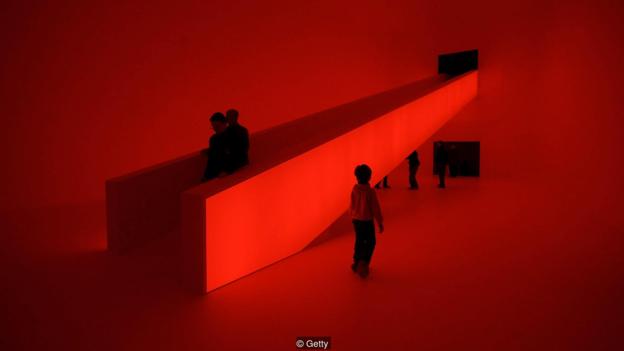

A show currently on view at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Endless Summer, further complicates the art historical narrative of art movements from the time, focusing on a cult movement called California Minimalism. Also known as Finish Fetish or Light and Space art, the works are shiny, colourful and industrial, derived from muscle cars and surf culture in Los Angeles but also psychedelia. The movement didn’t fit readily into the art historical narrative of minimalism or pop art – reactions against Abstract Expressionism – nor to the handcrafted aesthetics of the hippies. But it managed to bridge that divide. Although underappreciated, the movement influenced some of today's most famous living artists. Perhaps the best example is James Turrell, who took Light and Space to new heights.

The hippies were a majority white, middle-class group of young people with the undeniable luxury of being able to ‘drop out’.

The unifying characteristic of these movements, indeed of the countercultural revolution that shook the United States, and the world, beginning in the 1960s, was an anti-establishment sensibility unified against ‘the system’ or the status quo. Toward that end, these movements sought a unification of aesthetics and ethics, art and life, an idealism that inevitably fell short.

Hippie privilege

Despite the conservative rhetoric of the Reagan era that suggested Timothy Leary’s famous refrain “turn on, tune in, drop out” had been a moral and cultural failure, the 1960s and the psychedelic utopian visions of the hippies proved to be productive, says Blauvelt. “The utopian thinking of the counterculture was vitally important as a way of imagining another, better life, or a different way of living,” he says. “Not the existing everyday life, but rather a newly imagined life... liberated from things such as technocratic social repression, racial and sexual oppression, conventional capitalist notions of ownership and individual property.”

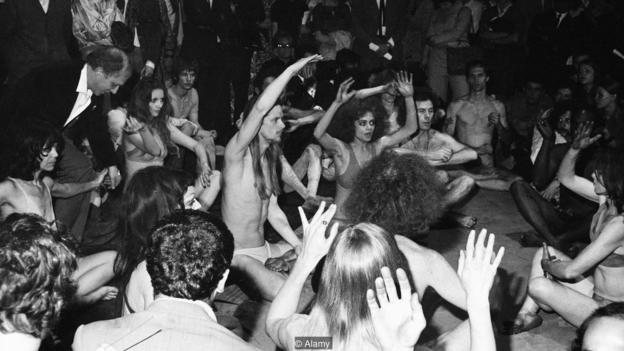

Hippies were synonymous with protest – but their ideology could be vague in comparison to, say, the Paris student protests of May 1968 (Credit: Alamy)

The 1960s marked a coming together of politics and counterculture, reminiscent of earlier modernist movements like dada and fluxus, though on a much larger scale. The hippies and their offshoot groups, more than any other anti-establishment group at the time, integrated art and life in a way in which the two were indistinguishable – an idea that carries through to contemporary art today.

It’s important to consider the context of the hippies, a majority white, middle-class group of young people with the undeniable luxury of being able to ‘drop out’. Even considering their participation in the civil rights and anti-war movements, the fact is that hippies had less at stake than those fighting for civil rights so that they could fully participate in society, not drop out. The hippies romanticised indigenous and eastern cultures (without considering the suffering of poverty) for their lack of modernity, experimenting with communal living and imaginary bohemia, creating an artificial marginality, which they saw as ethically righteous. Not to mention their unapologetic cultural appropriation.

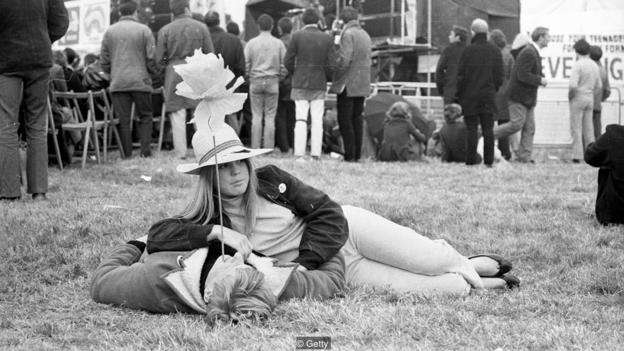

The hippies fuelled cultural changes more than they did political ones – their dress, hairstyles and music preferences were easily co-opted by the establishment (Credit: Getty)

The hippies acted as the extreme end on the spectrum of counterculture, like the dada and fluxus artists before them, staging ‘happenings’ (though they didn’t necessarily call them that) and purposefully alienating events in order to challenge and inflame everyday American sensibilities, which, arguably, made the protests of the Black Panthers, Chicanos and feminists less disruptive by comparison. Black, brown or LGBTQ activists could never have got away with the transgression of the hippies.

Freedom from the restrictions of the conservative, capitalistic, suburban US as represented by the Eisenhower ‘50s was shown in the surfing film Endless Summer (Credit: Alamy)

The anti-establishment, anti-academic and anti-mainstream ideas of the hippies were spread through zine-style publications and later in schools like the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California (1969) and the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics (1974) at the Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. Here, the status quo was exploded and reassembled into new ways of thinking that echoed through art, literature and life well into the 21st Century.

Light and space, man

The California Minimalism movement, while not commonly taught as part of the syllabus in university art history courses, was popular in southern California, says the curator of Endless Summer, Michael Darling. It has enjoyed a recent resurgence at art fairs and in major museum collections, not unlike the ideologies of the hippies. Yet the California Minimalists emerged from the macho 1950s muscle-car scene and Los Angeles surf culture, fitting into modernity more than hippie culture, Darling tells BBC Culture. “These guys mostly started out as abstract expressionists,” says Darling. So the artists were too old to be hippies, but they talked the talk, grew their hair and drank the Kool-Aid too.

Protesting against the Vietnam War was the most common form of political engagement the hippies chose (Credit: Photo by Greg Beckel, courtesy Walker Art Center)

The California minimalists, such as Robert Irwin in the show at the MCA, were psychedelic in their own way, creating introspective objects inspired by the same Zen and Taoist traditions as some of the hippies. Judy Chicago, also on view, made big psychedelic mandalas inspired by feminist idealogies germinated in the same hippie counterculture. It’s true, of course, that hippie aesthetics were anything but minimal. But the Light and Space artists were, as the Endless Summer show suggests, inspired by the combining and streamlining of life into art and vice versa.

Many former hippies, such as James Turrell, who schooled others on burning their draftcards, ended up creating non-political art, such as his piece Bridget’s Bardo (Credit: Getty)

The counterculture revolutions of the 1960s and early 70s crossed the oceans too, as masses of students took to the streets in Paris in the spring of 1968. Emory Douglas’s illustrations in The Black Panther newspaper had far-reaching influence on revolutionary groups in Latin America, Africa and Asia. Meanwhile, the California Minimalists managed to bridge the gap between minimal art, Andy Warhol’s pop and the hippie revolution while evading classification and, according to Darling, embedding in their meditative forms more critique than fantasy.

Lest we forget that the stench of revolution hung in the air amid the colourful rain of LSD and free love, we can look at the headlines of our own time. The politics of counterculture remain largely unchanged – tackling inequality, violence, climate change. Utopia is still a dream on the horizon and dystopia a scary possibility.

BBC

More about: hippies