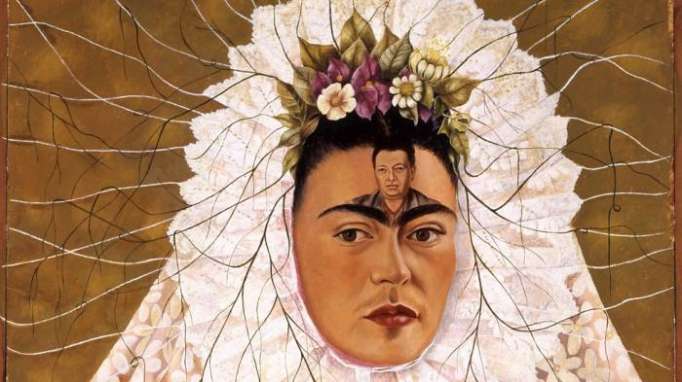

Frida Kahlo is now one of the most celebrated artists of the 20th Century – a feminist icon, and a trailblazer of modern art. It’s been a remarkable turnaround. Today she is far more famous than her husband but during her troubled lifetime it was the other way around.

“Wife of the master mural painter gleefully dabbles in works of art,” chortled a condescending newspaper report in 1933. This was typical of the attitudes of the age. If a female artist married a male artist, the press assumed she was just his helpmate – at best a supporting player, at worst a domestic drudge.

Kahlo’s art now receives the equal recognition it deserves, though equality came too late for her to relish it. However countless other female artists are still overshadowed by their artistic husbands, even though their art warrants equal billing. Attitudes are changing, but there’s still a long way to go. Here are four more female artists whose male partners hogged the limelight, and are now finally beginning to enjoy their (posthumous) just desserts.

Ray Eames & Charles Eames

Born in 1912 in California, Ray-Bernice Kaiser studied art at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where she met Charles Eames, a fellow student from Missouri. They married in 1941, established their own design studio in Los Angeles in 1947, and worked together until Charles died, in 1978 (Ray died in 1988, ten years later to the day).

Renowned for their iconic chairs, they were also architects, graphic designers and even filmmakers. Without Ray’s playful input, Charles never would have had the same impact, and he knew it. His work was all broad brushstrokes, hers was more detailed. He made inspired conceptual leaps – she gave their work the human touch.

As designers they were inseparable, but for a long time Charles got all the credit. ‘Anything I can do, Ray can do better,’ he said, but the media ignored his pleas. ‘America Meets Charles & Ray Eames’ (available on YouTube) is a good example of the patronising attitudes that Ray had to put up with. Broadcast in 1956 on NBC’s Home Show and presented by Arlene Francis it proves that in Fifties America, chauvinism wasn’t a purely male preserve.

The World of Charles and Ray Eames exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery, Barbican Centre, London, 2015 | Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Lee Miller & Man Ray

Born in New York in 1907, Lee Miller gave up a successful modelling career in America and moved to Paris in 1929 to become a photographer. She became Man Ray’s apprentice (and his lover) and quickly became his artistic equal, yet she only had one solo exhibition in her lifetime, in 1933.

Miller and Man Ray had a passionate, fiery relationship, and although the couple broke up in 1932 she remained a key figure in his life. She became a war photographer for Vogue, covering the London Blitz and the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps at Dachau and Buchenwald. After the war she suffered from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Miller remained close friends with Man Ray right up until his death in 1976. Seventeen years his junior, she died less than a year later, of cancer, aged 70. Her son Antony Penrose (from her marriage to the surrealist artist and curator Roger Penrose) restored her posthumous reputation, as the author of her biography and the curator of her photographic estate.

Lee Miller and American soldiers | Photo: David E Scherman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

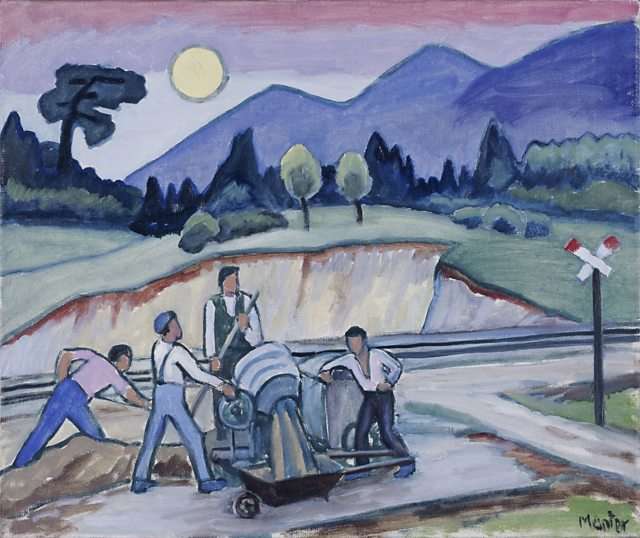

Gabriele Münter & Wassily Kandinsky

In her native Germany, Gabriele Münter is feted as one of the key figures of German Expressionism, but in the wider world she’s remembered, if at all, as the longstanding (and longsuffering) partner of Wassily Kandinsky.

Born in 1877 in Berlin, Münter went to Munich to become a painter, where she met Kandinsky, who’d come to Munich from his native Russia, abandoning a promising career as a lawyer to become an artist. Kandinsky left his wife for her and they set up home together in Murnau, a pretty town in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps.

Here they developed a new style of painting – simple and colourful, quite unlike the Impressionistic pictures they’d painted in Munich. Chauvinistic art critics tend to assume that Kandinsky inspired Münter, but there’s just as much evidence that it was actually the other way around.

Construction site on the Olympiastraße, Gabriele Münter, 1935 | Photo: Municipal Gallery in Lenbachhaus, Munich Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation, Munich © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Kandinsky wouldn’t marry Münter. Deported as an enemy alien at the start of the First World War, he returned to Germany after the war, married to another woman. Münter never married. She had no children. Kandinsky died in 1944 – the two lovers were never reconciled.

In 1957, on her 80th birthday, Münter gave her vast collection of paintings – including dozens of paintings by Kandinsky – to Munich’s Lenbachhaus. For all but a handful of her closest friends, the existence of this amazing collection was a complete surprise. The last survivor of German Expressionism, she died five years later, in 1962.

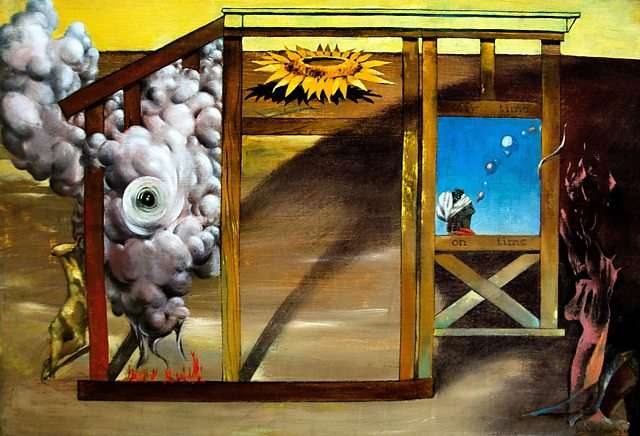

Dorothea Tanning & Max Ernst

Born in 1910 in Illinois, Dorothea Tanning was working as a commercial artist in New York when, in 1936, she saw an exhibition which changed her life. Fantastic Art – Dada & Surrealism at New York’s Museum of Modern Art inspired her to become a surrealist artist. In 1942, at a party in New York, she met the German émigré Max Ernst, one of the pioneers of Surrealism (Ernst was enchanted by her surreal self-portrait, Birthday).

On Time Off Time, Dorothea Tanning, 1948 | Photo: Peter Horree/Alamy Stock Photo

Tanning and Ernst married in 1946, and in 1949 they moved to France. Here, her art became more abstract. She also branched out into sculpture. After Ernst died, in 1976, aged 84, Tanning returned to New York. She’d always been a writer as well as an artist, and now she focused on her writing, publishing novels and poetry.

Tanning died in 2012, at the grand old age of 101, shortly after the publication of her latest book of poems. "Women artists? There’s no such thing," she said in 1990. "It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as 'man artist' or 'elephant artist'. You may be a woman and you may be an artist, but the one is a given and the other is you."

Read the original article on BBC.

More about: culture