On 2 May 1945, three soldiers and a photographer from the Red Army climbed onto the roof of the Reichstag in Berlin, a city they had just liberated from the Nazis. One soldier scrambled up a small tower, lifting aloft what appeared to be a Soviet flag. Behind him, eerie silhouettes of German heroes sculpted from stone took perpetual strides over the edge. The image taken in that moment went on to become a classic of war photography – and an interesting lesson in the blurred lines between truth and history.

Yevgeny Khaldei, Banner of Victory, Berlin, May 1945 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

Yevgeny Khaldei’s Banner of Victory appears in a new exhibition, Masterpieces of Soviet photography, at the Atlas Gallery in London. “It has such a great story attached to it, and a sense of mystery as well,” Atlas co-founder Ben Burdett tells BBC Culture. “It was a staged image – but staged for good reasons, because on the occasion when the banner was first raised, there wasn’t a photographer to capture the event. So the photographer went back the next day with the soldiers and restaged it because they wanted to have pictures of the Soviet banner over the Reichstag.”

Lacking a banner, the soldiers carried a piece of fabric later said to have been stitched together from three red tablecloths by the uncle of the photographer, with the hammer and sickle sewn on. According to the New York Times, Khaldei’s father and sisters had been killed by the Nazis – after seeing the photo of the Iwo-Jima flag raising taken by Joe Rosenthal just over two months earlier, he asked his uncle to create the makeshift flag and took it to Berlin so he could craft his own version of the iconic image.

Max Alpert, Combat!, 1942 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

“That became one of the most historic pictures of the war,” says Burdett. “And later, it emerged that at the time the soldiers had taken valuables from dead Germans, and the man in the foreground of the photo was wearing looted watches on his wrists. Subsequently, the Russian authorities decided it wasn’t what they wanted to be seen because it showed the soldiers taking valuables off the German soldiers. Later versions of the image were retouched: there is one version that shows the soldier with three watches – two on one wrist and one on the other – but most of those in circulation just have him wearing one watch, or none. It’s similar to Robert Capa’s dying solder, it’s the Russian version of it in a way – it’s a classic war picture.”

Reality bites

The photograph represents the ambiguity that threads together the other images in the exhibition, which are all drawn from the personal collection of the 95-year-old photographer Lev Borodulin. They stridently proclaim a strong Soviet Union – and simultaneously suggest nuances through experimental techniques. “Sometimes there is a first impression before a completely different picture is revealed when you know its history,” exhibition co-curator Maya Katznelson tells BBC Culture. “Soviet photographers produced real masterworks while creating the grandiose myth of Soviet civilisation. I think their activities are akin to heroism. To make, on the one hand, ideologically correct photographs, and on the other, within the narrow limits allowed, to seek maximum artistic expression.”

Lev Borodulin, Pyramid, Moscow, 1954 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

“Borodulin was a Soviet-era photographer himself, who took a lot of now well-known images of the 1950s to 1970s living in Soviet Russia – predominantly sporting events, anything athletic and generally heroic,” says Burdett. Driven by what Atlas describes as a “quest to collect and preserve images from a time when art was restricted to serve a Soviet socialist agenda”, Borodulin has amassed a collection over the past 70 years that contains around 10,000 images. It largely spans a period from the Russian Revolution to the 1960s, with photos gathered from magazines, archives and picture agencies like TASS.

“This collection saved many photographs from destruction, it was one of the first collections of Soviet photography,” says Katznelson. While covering a range of periods, for her the images from World War Two are particularly striking. “The time, when on the verge of life and death, photojournalists created masterpieces. Some of this work served to lift the spirit of the whole country; some has been hidden in the archives for a long time, and not seen the light for tens of years after the end of the war.”

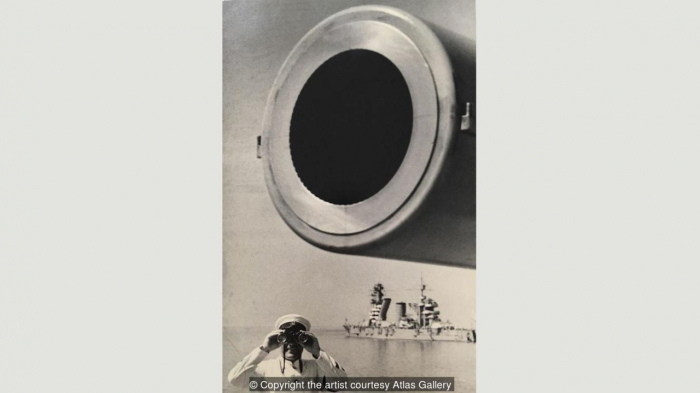

Yakov Khalip, Torpedo, The Baltic fleet, 1936 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

Borodulin finds special meaning in those images. “For me it is a very personal matter,” he tells BBC Culture from his home in Tel Aviv. “Many of my relatives were killed, if not all of them, I was injured twice, I was in the detachment that fought from Moscow to Berlin. It changed my life and the life of the country, and it changed the lives of all the people I knew. And I want people not to forget about it.” When Khaldei captured the fall of Berlin in his photo, there was still crossfire at the Reichstag: according to Borodulin, Khaldei risked his life to create the image. They later became close. “Khaldei was my personal friend, we spent many hours together remembering the war… and each time I came to the small photographic studio where he was living I saw this image, probably one metre wide by size, and we sat in front of it.”

Samary Gurary, Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin in Yalta, 1945 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

The collection offers a different way into Russian history. “It’s vast, covering the whole of the Stalin era, the whole of the Soviet period, World War Two, the Cold War and beyond,” says Burdett. “Some were taken in the darkest years of the Stalin era – from a historical point of view they represent an amazing resource for seeing the development and construction of modern Russia, particularly through heavy industry and agriculture.”

Semyon Fridlyand, Volzhanocka (Girl from the Volga region) (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

But Burdett and Katznelson were particularly drawn to another aspect of the collection, beyond historical record. “We were more interested in the development of the aesthetic of Soviet photography, and the artistic approach: the Constructivists, the October Group – the Russian equivalent to the Bauhaus,” says Burdett. “We were picking out works by masters of the medium such as Arkady Shaikhet, Yakov Khalip, Alexander Rodchenko and Boris Ignatovich.”

Alexander Rodchenko, Lily Brik, 1926 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

One central element of this Soviet aesthetic was dictated by the political landscape in which the photographers were working. “A common characteristic of a lot of the pictures is this rather fake triumphant exuberance that the photographers tried to capture in the faces of the people that they photographed. It’s a very obvious aspect of the images, that they have this propaganda element. It’s an aesthetic that’s become quite fashionable because it’s odd – it’s very melodramatic.”

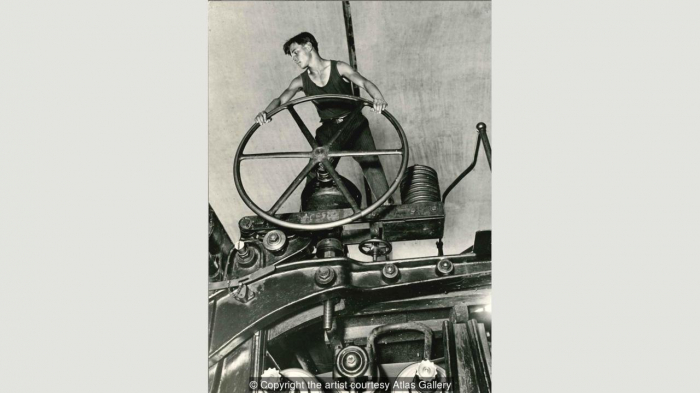

Arkady Shaikhet, Komsomol Member at the Wheel, Balakhna, 1929 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

But there’s another key element in Soviet photography that is far removed from the triumphal expressions of a powerful state. “In many ways, what characterises it is a degree of experimentation and improvisation which you don’t see in the West,” says Burdett. “Russian photographers developed this distinct view of photography which involved different approaches like unusual cropping and camera angles – a lot of the time the angles are diagonally framed rather than square; they’re looking up or down at subjects rather than straight on; they use photo montage and collage a lot.”

Alexander Rodchenko, Fire Escape, 1925 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

Alexander Rodchenko, Fire Escape, 1925 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

The Constructivists “identified themselves with the political revolution as innovative artists, and intended to build a new world with the means of new art”, according to Katznelson. The October Group radically changed the press. “For ten years – 1925-1935 – Soviet press photography was the most avant-garde in the world.”

Alexander Rodchenko, A Girl with Leica, 1934 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

Even when the avant-garde fell out of favour, photographers were pushing boundaries. According to Katznelson, “it was a time of ‘socialist realism’ – realistic in form and socialist in content… [and] the portrait was supposed to radiate optimism, the will to win and strength of mind”.

Yakov Kahlip, On Guard, 1937 (Photograph based on a design by Rodchenko) (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

The demands of propaganda in a way encouraged experimentation, argues Burdett. “Photographers were challenged to create work that looked triumphant and positive, so a lot of the photography shows life in a very dramatic light – part of that comes from using these unusual angles. Looking up or down at subjects gives a dramatic view of what’s going on in the pictures.”

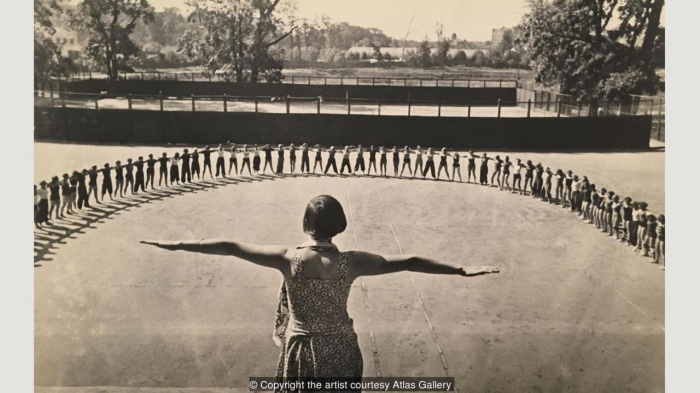

Vladislav Mikosha, Morning Exercise, 1937 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

“Through Soviet photography you can trace not only the history of the country, but also the change of ideological priorities. What to shoot and how to shoot,” argues Katznelson. Even by the 1960s, an age of liberation still had its restrictions, as Borodulin recalls when asked which of his own photos he particularly likes. “Probably one of my favourites is a photograph which was censored as ‘flying ass’, of the diver. I took it at my first Olympic games in 1960 in Rome and that was the first time I went to a ‘capitalist’ country. I was so happy to do this, I was just starting my career as a photographer at Ogoniok magazine… and it was chosen to be the cover.”

Lev Borodulin, Diver on the cover of Ogoniok magazine (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

Yet it received criticism from Mikhail Suslov, the unofficial Chief Ideologue of the Communist Party, who wrote in Pravda, Borodulin remembers, “that it’s not good for Ogoniok to publish this type of photo, because it’s too avant-garde and too formalistic”. Despite that, he took it as praise. “In this small article I was called a master, they say ‘it’s not fitting for such a big master of photography as Lev Borodulin to take this type of picture’.”

Lev Borodulin, Diver, 1960 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

The most recent photo in the exhibition reveals how Russian society had evolved since the 1920s – and how this collection can offer a different perspective on history. “What distinguishes it from a similar collection of works of a similar period from the US, from Life Magazine, or from Europe in the Picture Post is that there aren’t any pictures of celebrities,” says Burdett.

Igor Snegirev, Yuri Gagarin, April 1961 (Credit: Copyright the artist courtesy Atlas Gallery)

“There were no pictures of Marilyn Monroe, or Elvis – there was no celebrity culture. Until you get to this amazing picture of Yuri Gagarin in 1961. It was almost not until that point that Russia had a celebrity, in the modern sense – he was the first one. He was extremely handsome and heroic looking, and the first man in space, so he became this celebrity hero figure in Russia – and that’s 1961 which is quite late in the development of popular culture worldwide. That’s almost the latest image in the collection, in a way it forms the end of an era.”

BBC

More about: Soviet