OCO-3, as the observer is called, was launched on a Falcon rocket from Florida in the early hours of Saturday.

The instrument is made from the spare components left over after the assembly of a satellite, OCO-2, which was put in orbit to do the same job in 2014.

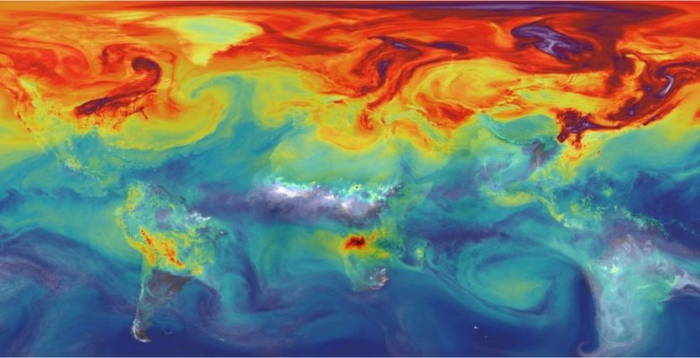

The data from two missions should give scientists a clearer idea of how CO2 moves through the atmosphere.

One way this will be achieved is through the different perspectives OCO-2 and OCO-3 will get.

The former flies around the entire globe in what's termed a sun-synchronous polar orbit, which leads to it seeing any given location at the same time of day.

The latter, on the other hand, because it will fly aboard the station, will only see locations up to 51 degrees North and South; and see them at many different times of day.

That's interesting because plants' ability to absorb CO2 varies during the course of daylight hours. OCO-3's dataset will therefore have much to add to that of its predecessor.

"Getting this different time of day information from the orbit of the space station is going to be really valuable," Nasa project scientist Dr Annmarie Eldering told BBC News.

"We have a lot of good arguments about diurnal variability: plants' performance over different times of day; what possibly could we learn? So, I think that's going to be exciting scientifically."

The Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO) missions are trying to tie down the uncertainties in the cycling of CO2 - how and where the greenhouse gas is emitted (sources), versus how and where it's absorbed (sinks).

Humans are driving an imbalance in this cycle, increasing the concentration of the gas in the air.

Currently, anthropogenic activities pump out just under 40 billion tonnes of CO2 year-on-year, principally from the burning of fossil fuels.

Only about half of this sum stays in the atmosphere, where it adds to warming.

About half of the other half is absorbed into the ocean, with the remainder pulled down into land sinks. But these "budgets" are imperfectly characterised. Some sizeable sources and sinks - both human and natural - need a fuller description.

The OCO instruments incorporate spectrometers that break the sunlight reflected off the Earth's surface into its constituent colours, and then analyse the spectrum to determine how much carbon dioxide is present.

The interpretation of the data is complex because it requires the use of models to explain how the gas is mixed through the atmosphere.

The space station instrument brings a new trick to the OCO observations - a swivelling mirror system that allows the spectrometer system to scan a much wider swath of the Earth's surface than would ordinarily be the case.

This "snapshot" mode means CO2 maps can be built up in a single pass over a target of special interest, such as a megacity - a task that will take OCO-2 several days.

"The snapshot mode allows us to grab snippets of data over an area of about 80km by 80km in two minutes. Right now we think we may spend about a quarter of our time making these mini maps, up to 100 a day," Dr Eldering said.

OCO-3 will be positioned on the Japanese segment of the space station. Its mission lifetime is pretty fixed at three years, therefore. That's because the berth it is taking up on the observation platform is already booked for a future instrument.

Carbon monitoring will, however, see many more satellite systems launched in the coming years.

Europe is planning a constellation of observers in its Sentinel series that will map CO2 over a much wider area than OCO, but still with the same high precision.

This orbiting network would even make it possible to police individual countries' commitments to reduce carbon emissions under international agreements such as the Paris climate accord of 2015.

More about: Nasa