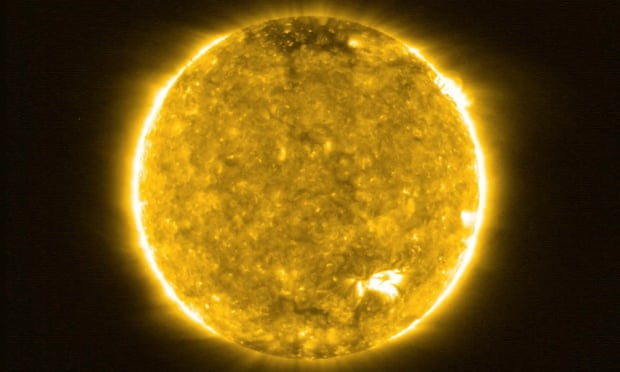

The observations, beamed back from the Solar Orbiter spacecraft, which is a joint Nasa and European Space Agency (ESA) mission, could help resolve why the sun’s atmosphere is so staggeringly hot compared to the surface – a central paradox in solar physics. Miniature flares have been proposed as a theoretical explanation for the so-called coronal heating problem, but until now no telescope has had a good enough resolution to observe the sun’s atmosphere in sufficient detail.

The latest footage, taken at 77m kilometres (48m miles) above the solar surface between the orbits of Venus and Mercury, reveals flickering beacons, each spanning just a few hundred kilometres across and lasting minutes, before fizzling out again.

“The campfires are little relatives of the solar flares that we can observe from Earth, million or billion times smaller,” said David Berghmans of the Royal Observatory of Belgium, a principal investigator on the mission. “The sun might look quiet at the first glance, but when we look in detail, we can see those miniature flares everywhere we look.”

The $1.3bn mission was launched in February and will ultimately provide the first glimpses of the sun’s uncharted north and south poles when the probe reaches a vantage point above the planetary plane late next year.

As it moves closer to the sun, the spacecraft will be exposed to scorching temperatures, requiring its camera and other instruments to be housed behind a titanium heat shield coated in a substance called SolarBlack, made from charred animal bones. The instruments and camera peer through peepholes that shut whenever there is a risk of them overheating.

The latest images show what is happening in the lower layers of the sun’s atmosphere, known as the corona, that extends millions of kilometres into outer space. The coronal temperature is more than a million degrees Celsius, orders of magnitude hotter than the surface of the sun, which is a relatively cool 5,500C. Solar physicists have been trying for decades to resolve the mystery of why the corona is quite so hot.

“One of the theories is that you have all these really small solar flares going off all the time all over the sun,” said David Long of UCL’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory, a principal investigator on the mission. “What we’re seeing in these images are there are very small brightenings going off all over the sun.”

It is possible that the flares could provide enough energy to heat up the corona to its observed extreme temperature. Further observations and analysis are needed to confirm whether this is the case.

Solar Orbiter is now on a tour of the inner solar system on the far side of the sun, meaning it is out of everyday contact with the Earth. That will bring it into an orbit about 42m kilometres from the sun over the next two years. By 2025, its orbit will have an inclination of 17° – high enough to take images of the sun’s poles – and if the mission is extended it could reach an inclination of 33°. Mission scientists say that observations of the poles could reveal the processes driving the Sun’s 11-year cycle of activity.

More about: #theSun