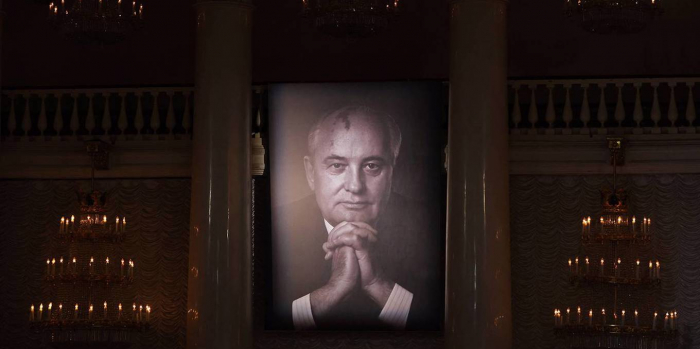

Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union’s last leader, was buried last month at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow next to his wife Raisa and near fellow Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. To no one’s surprise, Russian President Vladimir Putin did not attend the funeral. Novodevichy, after all, is where “unsuccessful” Soviet leaders had been consigned to their final rest.

Putin’s snub reminded me of a conversation I had two decades ago during a midnight stroll through Red Square. On impulse, I asked the army officer stationed in front of Lenin’s Tomb who was buried in the Soviet Necropolis behind it, and he offered to show me. There, I saw a succession of graves and plinths for Soviet leaders: from Stalin to Leonid Brezhnev, Alexei Kosygin, and Yuri Andropov. The last plinth was unoccupied. “For Gorbachev, I suppose?” I asked. “No, his place is in Washington,” the officer replied.

Ironically, Gorbachev has been lionized in the West for accomplishing something he never set out to do: bringing about the end of the Soviet Union. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990, yet Russians widely regarded him as a traitor. In his ill-fated attempt at a political comeback in the 1996 Russian presidential election, he received just 0.5% of the popular vote.

Gorbachev remains a reviled figure in Russia. A 2012 survey by the state-owned pollster VTsIOM found that Gorbachev was the most unpopular of all Russian leaders. According to a 2021 poll, more than 70% of Russians believe their country had moved in the wrong direction under his rule. Hardliners hate him for dismantling Soviet power, and liberals despise him for clinging to the impossible ideal of reforming the communist regime.

I became acquainted with Gorbachev in the early 2000s when I attended meetings of the World Political Forum, the think tank he founded in Turin. The organization was purportedly established to promote democracy and human rights. But in practice, its events were nostalgic reminiscences where Gorbachev held forth on “what might have been.” He was usually flanked by other has-beens of his era, including former Polish leaders Wojciech Jaruzelski and Lech Wałęsa, former Hungarian Prime Minister Gyula Horn, Russian diplomat Alexander Bessmertnykh, and a sprinkling of left-leaning academics.

Gorbachev’s idea of a “Third Way” between socialism and capitalism was briefly fashionable in the West but was soon swamped by neoliberal triumphalism. Nonetheless, I liked and respected this strangely visionary leader of the dying USSR, who refused to use force to resist change.

Today, most Russians cast Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin as harbingers of Russia’s misfortune. Putin, on the other hand, is widely hailed as a paragon of order and prosperity who has reclaimed Russia’s leading role on the world stage. In September, 60% of Russians said they believe that their country is heading in the right direction, though this no doubt partly reflects the tight control Putin exercises over television news (the main source of information for most citizens).

In the eyes of most Russians, Gorbachev’s legacy is one of naivete and incompetence, if not outright betrayal. According to the prevailing narrative, Gorbachev allowed NATO to expand into East Germany in 1990 on the basis of a verbal commitment by then-US Secretary of State James Baker that the alliance would expand “not one inch eastwards.” Gorbachev, in this telling, relinquished Soviet control over Central and Eastern Europe without demanding a written assurance.

In reality, however, Baker was in no position to make such a promise in writing, and Gorbachev knew it. Moreover, Gorbachev repeatedly confirmed over many years that a serious promise not to expand NATO eastward was never made.

In any case, the truth is that the Soviet Union’s control over its European satellites had become untenable after it signed the 1975 Helsinki Final Act. The accord, signed by the United States, Canada, and most of Europe, included commitments to respect human rights, including freedom of information and movement. Communist governments’ ability to control their population gradually eroded, culminating in the chain of mostly peaceful uprisings that ultimately led to the Soviet Union’s dissolution.

Yet there is a grain of truth to the myth of Gorbachev’s capitulation. After all, the USSR had not been defeated in battle, as Germany and Japan were in 1945, and the formidable Soviet military machine remained intact in 1990. In theory, Gorbachev could have used tanks to deal with the popular uprisings in Eastern Europe, as his predecessors did in East Germany in 1953, Hungary in 1956, and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Gorbachev’s refusal to resort to violence to preserve the Soviet empire resulted in a bloodless defeat and a feeling of humiliation among Russians. This sense of grievance has fueled widespread distrust of NATO, which Putin used years later to mobilize popular support for his invasion of Ukraine.

Another common misconception is that Gorbachev dismantled a functioning economic system. In fact, far from fulfilling Khrushchev’s promise to “bury” the West economically, the Soviet economy had been declining for decades.

Gorbachev understood that the Soviet Union could not keep up with the US militarily while satisfying civilian demands for higher living standards. But while he rejected the Brezhnev era’s stagnation-inducing policies, he had nothing coherent to put in their place. Instead of facilitating a functioning market economy, his rushed abandonment of the central-planning system enriched the corrupt managerial class in the Soviet republics and led to a resurgence of ethnic nationalism.

To my mind, Gorbachev is a tragic figure. While he fully grasped the immense challenges facing Soviet communism, he had no control over the forces he helped unleash. Russia in the 1980s simply lacked the intellectual, spiritual, and political resources to overcome its underlying problems. But while the Soviet empire has been extinct for 30 years, many of the dysfunctions that contributed to its demise now threaten to engulf the entire world.

Robert Skidelsky, a member of the British House of Lords and Professor Emeritus of Political Economy at Warwick University, was a non-executive director of the private Russian oil company PJSC Russneft from 2016 to 2021. The author of a three-volume biography of John Maynard Keynes, he began his political career in the Labour party, became the Conservative Party’s spokesman for Treasury affairs in the House of Lords, and was eventually forced out of the Conservative Party for his opposition to NATO’s intervention in Kosovo in 1999.

More about: