How high-fat ketogenic diet acts on the brain to help epilepsy

According to early-stage research, the high-fat ketogenic diet may also help several other brain conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. The diet seems to have slowed or even stopped cancer growth in a few people with brain tumours who started to follow it to control seizures. When given to mice with tumours, it amplified the effects of radiotherapy. The results are so intriguing that a small trial of the diet in people with brain tumours is planned for next year.

But by far the most common use is for epilepsy. The ketogenic diet has been used in children with severe epilepsy since the 1990s. Two-thirds of those who try it see their number of seizures fall by half or more. In some cases, as happened for Matthew, children can later be weaned off the diet without their epilepsy becoming worse again.

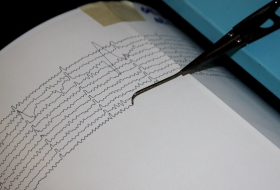

Until now, the mechanism behind these effects had been a mystery. Now researchers have discovered that one of the breakdown products of fat binds to molecules on the surface of brain cells, calming the storm of electrical activity that can cause epileptic seizures.

Calm the storm

Our cells usually get their energy from glucose, which comes from the carbohydrates we eat. But when these aren’t available, the liver breaks down fat into fatty acids and ketones, so that our cells can burn ketones for energy instead. In epilepsy, the thinking has long been that these ketones somehow make neurons in the brain less likely to fire, preventing seizures.

But there was still a puzzle: higher blood ketone levels in those following the diet don’t necessarily correlate with fewer seizures. Instead, it has been suggested that a fatty acid called decanoic acid is responsible for the effect. Previous work found that directly feeding this compound to mice with a version of epilepsy reduced their seizures.

Now laboratory tests using frog cells have shown that decanoic acid directly binds to a molecule that is found on the surface of brain cells and is known to be involved in spreading electrical impulses between different neurons. When decanoic acid binds to it, it reduces the flow of electrical current into the cell via this molecule. “It reduces the chance of a neuron firing,” says Robin Williams of Royal Holloway, University of London.

His team’s finding could lead to easier dietary regimes that get the same result. “It’s a strong theory, and if it translates into practice we could use a more acceptable diet,” says Helen Cross of Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London, who wasn’t involved in the research. She plans to trial giving decanoic acid directly to people.

This could enable more people with epilepsy to benefit from the diet’s effects. The ketogenic regime seems to work for adults too, but few follow it because it’s so hard to stick to. In the standard version, people have to make sure around three-quarters of their food is fat. “It can be daunting,” says Emma Williams. “You have to weigh every gram of food.”

But simply adding decanoic acid to food won’t be enough. Under a typical high-carb diet, the body would still rely on glucose for energy, and store away the decanoic acid as fat. To make sure that the decanoic acid gets into the brain, people would still need a relatively low-carb diet — but not as low as the current ketogenic diet, says Robin Williams.

For instance, in Cross’s trial, due to start next year, children with epilepsy will be given decanoic acid twice a day, in the form of a yogurt-like drink. They won’t be able to eat sugary foods, but will be able to eat plenty of carbs like wholemeal bread and pasta, which release glucose into the blood more slowly. “It’s a lot more acceptable,” says Cross. “And there’s no measuring involved.”