The research, presented April 25 at the Web Conference in Lyon, France, investigated the data-sharing disclosures of more than 200,000 websites — the Arkansas state government homepage, for instance, and the Country Music Association site. In specific, it looked at how these sites shared data with third parties, such as advertisers and data brokers, as well as how those sites described their privacy policies.

For this analysis, privacy researcher Timothy Libert used a software tool called webXray to trace data transmissions from each website to third-party data collectors. Of 1.8 million data transmissions tracked, only 14.8 percent were sent to third parties specifically mentioned in those sites’ privacy policies. The rest of the data went to third parties that users wouldn’t know about even if they read the sites’ policy statements.

Libert also found that data transfers to widely familiar third parties, like Google, Facebook and Twitter, were more likely to be disclosed than transfers to obscure entities. For instance, while 38.3 percent of data transmissions sent to Google were disclosed, the disclosure rate for the data broker Acxiom was about 0.3 percent.

Covert collection

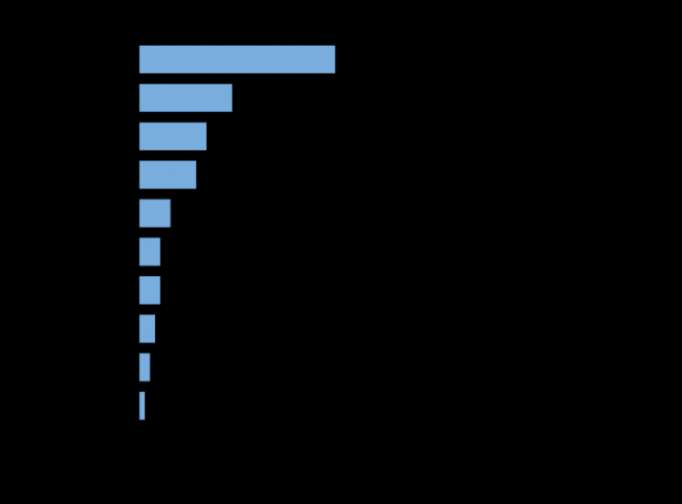

An analysis of data transfers from over 200,000 websites to third-party data collectors (some listed above) shows that the websites rarely disclose in their privacy policies exactly where they are sending your data. The data collector most likely to be disclosed was Google, with about 38 percent of data transfers coming from websites that named Google in their policy statements. More obscure entities, like Quantcast, showed far lower rates of disclosure. Fifteen other data collectors tracked in the study didn’t even break 1 percent.

Even if website privacy policies listed all the third parties they shared data with, users still may not know exactly how their information gets spread around, says Libert, of the University of Oxford. That’s because third parties that receive user information from websites can then share that data with other entities. Getting online is “sort of like tossing confetti in the air,” Libert says. “There’s no way to know where your data ends up.”

Data-sharing relationships between sites and third parties change so rapidly that it’s virtually impossible for privacy policy authors to keep up, says Christo Wilson, a computer scientist at Northeastern University in Boston not involved in the work. “The only true disclosure is, ‘We sell your data, and we don’t know where it goes,’” he says.

Those still inclined to read privacy policies may want to set aside some time; it takes nearly 90 minutes on average to read a website’s privacy statement along with the policies of its known third-party data collectors, Libert found. “The idea that users can keep track of this, read policies, and make decisions is pure fiction,” he says.

Internet users can try to keep their data out of advertisers’ hands “with things like hardcore ad-blocking,” says Wilson. But ad-blocking software may not ward off all advertisers, he adds. “It just gets more and more clear that we need things like GDPR,” or General Data Protection Regulation. This new set of rules that restricts how tech companies can collect and use personal data takes effect across the European Union in May (SN Online: 4/15/18).

Libert says the United States needs an agency to oversee the data-sharing ecosystem, similar to how the U.S. Food and Drug Administration monitors pharmaceutical industry activity. “I can buy medicine at the store and not have to sit down with a chemistry textbook and look up every compound and see its effects — somebody at the FDA does that,” he says.

Science News

More about: science