Ancient stone tools and the remains of a butchered rhino discovered on the island of Luzon have sparked debate among scientists about the early colonisation of South East Asia.

These ancient humans were likely closely related to Homo erectus, as modern humans did not arrive in the region until around 50,000 years ago.

The new study, led by scientists at the French National Museum of Natural History and published in the journal Nature, has also prompted a re-think of tiny ancient humans popularly known as ‘hobbits’.

“Our hypothesis is that the ‘hobbit’ ancestors came from the north, rather than travelling eastward through Java and Bali,” said Dr Gerrit van den Bergh, a palaeontologist at the University of Wollongong who contributed to the work.

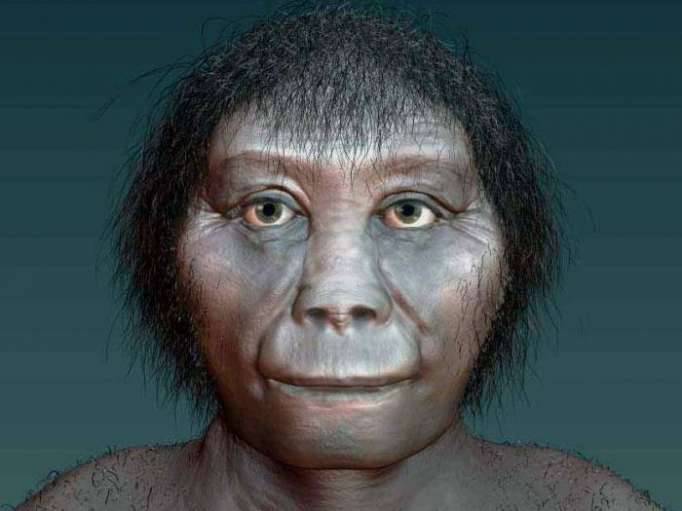

Homo floresiensis – the scientific name for these small human ancestors – were found on the Indonesian island of Flores, which is around 1,200 miles south of Luzon.

Until recently, it was assumed ancient human ancestors would not have been able to reach the Philippines due to their lack of boats.

However, this thinking was turned on its head in 2003 when the first hobbit remains were discovered, followed by other remains of ancient humans from neighbouring islands.

Further exploration has unearthed evidence that hobbit ancestors were present on Flores around the same time as the newly discovered hominins were present on Luzon.

This suggests ancestral humans came to Flores from the north, hopping from the mainland across Luzon and other islands until they reached the southern part of Indonesia.

There could therefore be a link between the humans inhabiting Luzon and the hobbits that ended up flourishing further south.

As for how humans crossed the vast expanses of ocean between the two islands, Dr van den Bergh and his team think it is unlikely they constructed rafts of any sort. Instead, he suggests an altogether more extreme mode of transport.

“They may have been caught in a tsunami and carried out to sea – those kinds of freak, random events are probably responsible for these movements of humans and animals,” he said, citing the case of people who were dragged out to sea by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

“This region is tectonically active so tsunamis are common and there are big ones every hundred years or so.”

These ideas are supported by the pattern of animals found living on the islands of South East Asia, which appears to mimic the proposed dispersal pattern of humans.

“If you look at the fossil and recent faunas you see that there is an impoverishment as you go from north to south,” said Dr van den Bergh.

“On Luzon you find fossils of stegodons [relatives of elephants], elephants, giant rats, rhino, deer, large reptiles and a type of water buffalo,” he said.

“Then on Flores, you only had stegodons, Komodo dragons, humans and giant rats, that’s all.

“If animals did reach these islands by chance, by entering the sea and following the currents south, then you would expect the further south you go the fewer species you would find – and that’s what we see.”

There are still a lot of unknowns in researchers’ understanding of the first colonisation of South East Asia by humans.

However, Dr van den Bergh said it is a region that provides scientists with excellent insights into the evolution of our ancient relatives.

The Independent

More about: hobbits