Scientists have found older adults fared better when it came to cognitive tasks if they clocked up higher levels of daily activity on a wrist-based tracker – something the researchers said picked up everything from exercising to mundane tasks like chopping onions.

What’s more, the benefits of movement remained even when the team took into account the level of tell-tale signs of Alzheimer’s and other dementia-related diseases in the brain.

Co-author of the Rush University study, Dr Aron Buchman, said the results showed that “even though we don’t have a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and we know people are accumulating it, you can mitigate the deleterious effects … by having more activity.”

But it’s not only moving more which is linked to better scores for traits like thinking, comprehension and and memory: the team found better motor abilities, as measured through tasks like the strength in gripping items or speed of turning on the spot, also seemed to offer protection when it comes to cognitive prowess.

The team say previous work has shown that moving more is linked to a lower risk of dementia, and slows the decline in thinking and memory skills in older adults as they age – but the latest research goes further.

Writing in the journal Neurology, the authors report how they came to their conclusions after studying 454 individuals, 191 of whom had dementia, as they progressed through older age to death – which on average occurred around the age of 91.

The researchers looked at participants’ data collected, on average, two years before they died – including their prowess in a series of 21 cognitive tests, as well as seven days of activity data and motor skill assessment.

The results show those without dementia clocked up higher levels of activity, on average, than those with the condition.

After taking into account factors such as age, sex and education, the team found that both the motor abilities of participants and their level of physical activity were separately linked to thinking and memory abilities, meaning they had a stronger impact together than either alone.

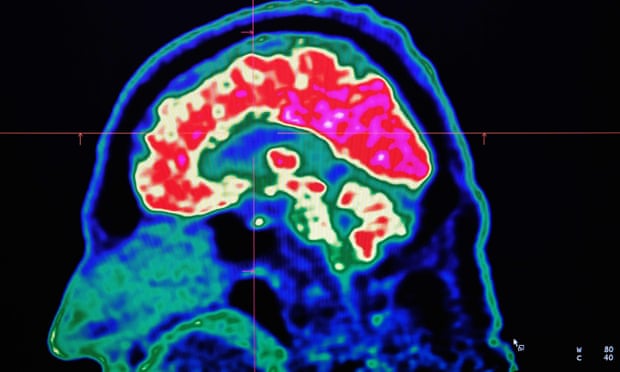

When the team looked at the brains of the participants after they died, they found those with more of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease had scored worse on the thinking and memory tests. But among those with the same extent of the disease, participants with better motor abilities or more physical activity had fared better cognitively. The beneficial link held even when other dementia-related diseases of the brain linked to cognition were considered, including the presence of proteins called Lewy bodies. However, there was no sign that activity or motor skills were changing the impact of the disease itself on thinking or memory abilities.

The team say more work is now needed to unpick how and why physical activity and motor skills might offer a protective effect on cognition, contributing to so-called resilience or “cognitive reserve”.

“The concept of resilience is an empowering concept,” said Buchman, indicating it offered individuals the chance to make changes to mitigate problems.

A limitation of the study was that it only looked at data relating to participants’ activity levels and motor skills at one point in time, and did not take into account how active participants had been earlier in their life. It is also not clear whether particular activity types, or their durations, would offer greater benefits than others or whether worse cognition might also lead people to move less.

Dr James Pickett, head of research at the Alzheimer’s Society, welcomed the study. “What’s fascinating about this research is that it suggests physical activity might not slow down dementia-related changes in the brain, but could help the brain cope with these changes,” he said.

Pickett added that it’s important people are supported to introduce more activity into their lives. “For anyone concerned about keeping their brains healthy in later life, we encourage eating a balanced diet, avoiding smoking and excessive drinking, and getting that step count up.”

The Guardian

More about: dementia