Scientists believe that tidal forces exerted on this underground sea by Jupiter`s largest moon Charon may have been to blame for Pluto rolling over on its axis.

The findings are based on observations by Nasa`s New Horizons, which made an unprecedented flyby of Pluto last year.

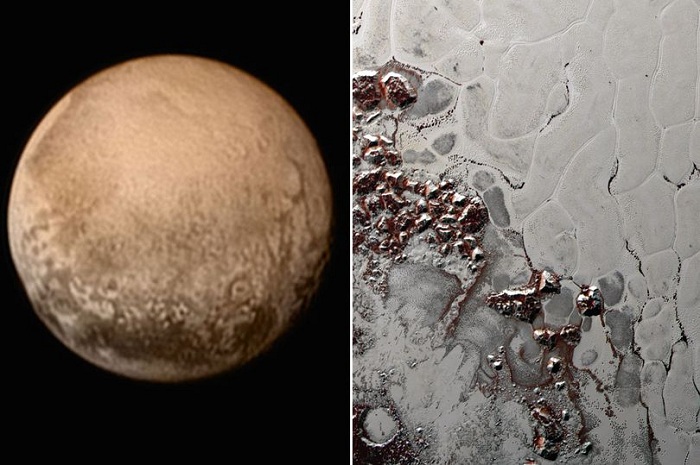

The study, published in this week`s journal Nature , focuses on a 600-mile basin in the left lobe of Pluto`s heart-shaped region, named Sputnik Planitia after the Russian satellite that launched the Space Age in 1957.

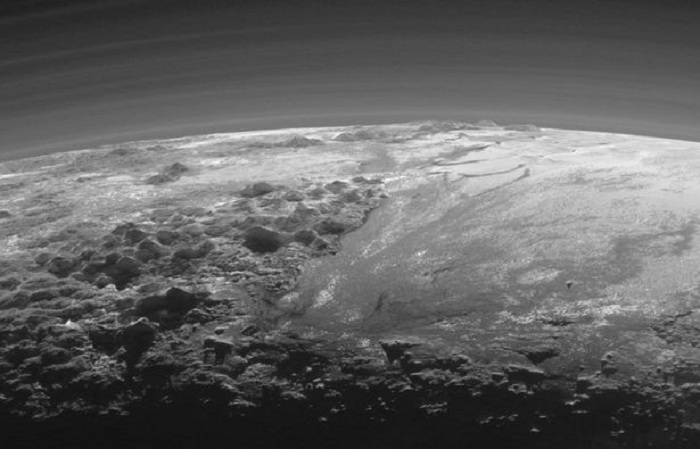

A Plutonian Landscape

Sputnik Planitia is aligned with Pluto`s tidal axis - so much so that it is unlikely to be coincidence, according to the researchers.

More likely, the nitrogen ice-coated basin has extra mass below the surface, causing Pluto to reorient itself and have Sputnik Planitia on the opposite side of the dwarf planet as Charon.

"It`s a big elliptical hole in the ground, so the extra weight must be hiding somewhere beneath the surface. And an ocean is a natural way to get that," said lead author Francis Nimmo, from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Nimmo suspects the ocean is primarily water with some ammonia or other "antifreeze" thrown in. Slow refreezing of this ocean would conceivably crack the planet`s shell - a scenario consistent with photos taken by New Horizons.

The blocky ice plains comprising Sputnik Planum are geologically young, offering strong evidence for active processes beneath Pluto’s surface.

The scientists believe that subsurface oceans could also exist on other similarly sized worlds orbiting in the Kuiper Belt - a so-called twilight zone on the fringes of our solar system.

"They may be equally interesting, not just frozen snowballs," said Nimmo.

Meanwhile, closer to the sun, scientists from the Smithsonian Institution`s National Air and Space Museum have discovered a big new valley on Mercury, using images taken by Nasa`s Messenger spacecraft.

The valley is more than 600 miles long, 250 miles wide and two miles deep.

A research team led by senior scientist Thomas Watters attribute the formation of the valley to surface buckling, caused by global contraction.

Earth has experienced this type of buckling, involving both oceanic and continental plates, Mr Watters said, but this may be the first evidence of it on Mercury.

The study was published in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

-1741770194.jpg&h=190&w=280&zc=1&q=100)