In a collaboration with Stanford University in the US, a team of scientists from the University of Sydney and Microsoft have used the newly found phase of matter - topological insulator - in shrinking an electrical component called a circulator 1,000 times smaller.

That's super good news when it comes to squeezing more qubits into a small enough space.

If you missed the fuss last year, a trio of physicists received the Nobel Prize for discovering that under certain conditions some materials could easily conduct electrons along their surface, but remain an insulator within.

Most importantly, they discovered cases where matter transitioned between states without breaking something called symmetry, as happens when water atoms rearrange into ice or vapour.

As we shrink electrical components down to virtually atomic scales, the way electrons move in different dimensions becomes increasingly important.

Enter the qubit – a chunky piece of electronics that uses the probabilities of an unmeasured bit of matter to perform calculations classical computers can't hope to match.

We can make qubits in a variety of ways, and are getting pretty good at stringing them together in ever larger numbers.

But shrinking qubits to sizes small enough that we can shove hundreds of thousands into a small-enough space is a challenge.

"Even if we had millions of qubits today, it is not clear that we have the classical technology to control them," says David Reilly, a physicist at the University of Sydney and Director of Microsoft Station Q.

"Realising a scaled-up quantum computer will require the invention of new devices and techniques at the quantum-classical interface."

One such device is called a circulator, which is kind-of like a roundabout for electrical signals, ensuring information heads in one direction only.

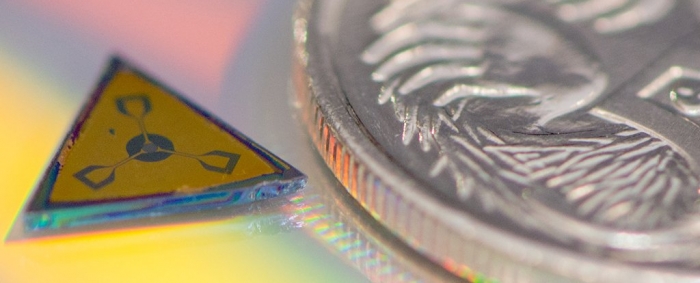

Until now, the smallest versions of this hardware could be held in the palm of your hand.

This is now set to change as scientists have shown a magnetised wafer made of a particular topological insulator could do the job, and be made 1,000 times smaller than existing components.

"Such compact circulators could be implemented in a variety of quantum hardware platforms, irrespective of the particular quantum system used," says the study's lead author, Alice Mahoney.

In many respects, we're still at the pre-vacuum-tube and magnetic tape phase of quantum computers – they're more promise than practical.

But if we keep seeing advances like this, it won't be long before we'll be bringing you news of quantum computers cracking problems which leave our best supercomputers gasping.

More about: #Quantum-Computer

-1741770194.jpg&h=190&w=280&zc=1&q=100)