Invitations to tender (ITTs) for the feasibility work will be sent out to industry in the coming weeks.

The European Space Agency hopes to put a list of satellites for implementation before ministers in late 2019.

Those platforms that are selected would launch in the mid-2020s.

Precisely how many of the six will make it to the launch pad will depend on the funds available, but Esa's Earth observation director is bullish about what can be achieved.

"I'm not thinking about down-selection at this stage," said Josef Aschbacher.

"I'm preparing six candidates and I want to offer ministers the six candidates at our meeting in 2019. I know that's a bold proposal, but that's what I want to do and then of course in the end it will be for our member states and the European Commission to decide what they want to do," he told BBC News.

As well as a CO2 mission, the so-called A/B1 studies will look at the potential of a thermal infrared sensor, a hyper-spectral imager, and three satellites that could have applications in polar regions - an L-band radar, a topography mission, and a passive microwave radiometer.

The topography satellite would essentially be an operational version of Cryosat, the current Esa altimeter spacecraft that has transformed knowledge about the shape and thickness of ice fields, such as Antarctic glaciers and Arctic sea-ice.

The radiometer would be an advance on ageing American and Japanese satellites that are presently used to measure the extent of marine floes.

L-band radar is effective in monitoring shipping lanes for hazards such as icebergs, among other uses.

The Sentinels are part of the European Union's ambitious Copernicus programme, which is developing a comprehensive "health check" for the planet.

The spacecraft data is also being used in member states to inform and enforce EU policies.

Five Sentinels are already flying. A sixth - a UK/Dutch-built platform to monitor air quality - will go up in a fortnight's time.

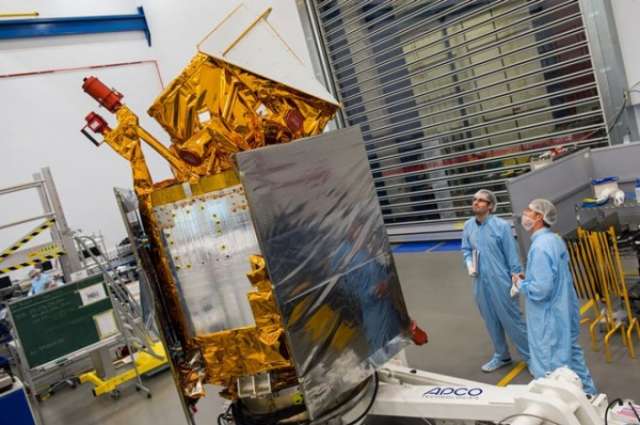

Still more spacecraft are already approved, funded and in various stages of construction.

The multi-billion-euro cost is shared 25-75% by Esa and the EU, with the space agency acting as the technical and procurement lead on the project.

In other words, it is an EU-owned endeavour that leans on the expertise of Esa.

The agency's Earth observation programme board green-lit the A/B1 studies last week, with an industrial policy committee then giving its own approval on Tuesday.

The release of ITTs to industry will be staggered to give companies time to make multiple submissions.

Esa and the Commission are looking for ideas that draw on some of the "new space" spirit that has recently seen several internet entrepreneurs enter the satellite business with innovative, low-cost platforms.

"As you know, I'm always on the look-out for new ideas, but it's clear also there are limits," said Dr Aschbacher.

"For CO2, for example, I don't think there is a commercial solution out there. It's unrealistic that any new space company would do the high resolution and accuracy required for the [climate negotiations] process and the Paris Agreement."

UK companies are urged not to be hesitant in joining consortia because of Brexit uncertainty.

Britain finds itself in a position where it is the largest contributor to Esa's Earth observation budget but also about to leave the EU.

The scale of its Esa subscription - which will be unaffected by Brexit - means it can expect substantial industrial return on any R&D work for the upcoming Sentinels.

But its departure from the EU on unfavourable terms could also then see that early work come to naught when the European Commission hands down the big contracts to build recurring satellites in the 2020s.

Britain's Prime Minister, Brexit Secretary and Business Secretary have all stated that they want the UK to continue in Copernicus (PDF) beyond the country's EU withdrawal in March 2019 and any transition period that may follow.

And national space officials have said companies and scientists should plan on the basis that continued involvement will be secured.

More about: #science